Admittedly, the pie is not as immediately mysterious or outwardly useful as pi, the never ending decimalised number chain that most people cannot name beyond two points.

Those who can list beyond the 1 and the 4, precocious children about whom movies will be later made in which they carry out feats of arithmetic wonder on panes of glass instead of pages, are venerated and extolled as masters of mathematical wonders, line tamers who trigonometrically tease shapes, wielding protractors like three-legged stools as they bravely thrust their heads into the gaping maul between the adjacent and opposite lines of a triangle.

Admirable qualities, for sure. But where is the love for the capable kid whose memory allows him or her to itemise the ingredients for a buttery short-crust filled with succulent morsels of stewed meat or sticky berries bursting forth with tart sweetness with each and every bite, eh?

March 14th

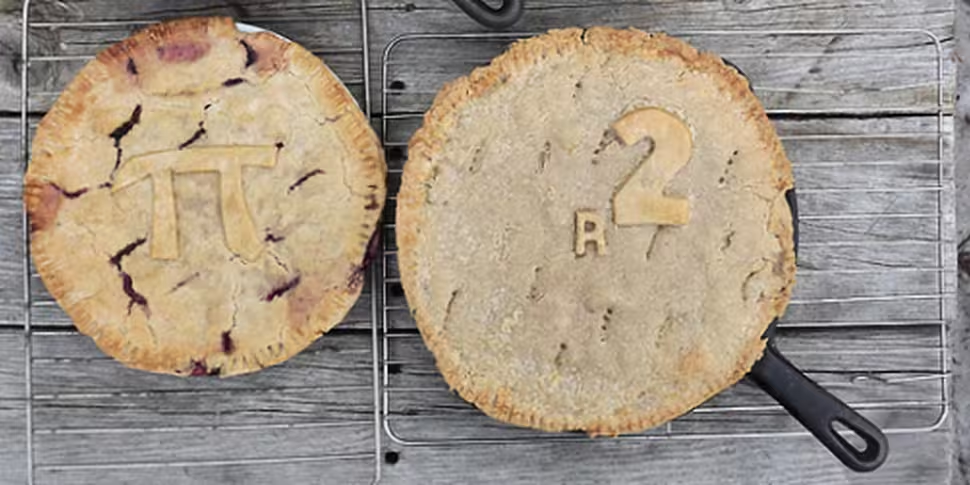

Today is Pi Day, March 14th, 3.14 by American calendars. Founded in 1988 by physicist Larry Shaw, the first Pi Day celebration was observed in the Exploratorium, a science museum in San Francisco, and saw mathematicians and enthusiasts parading around in a circle while carrying fruit pies. Like the formula itself, Pi Day has grown progressively bigger, ultimately recognised by the US House of Representatives in 2009 and declared an official national holiday.

Not to be outdone by a numeral now stretching to a trillion decimal places, pies also get their due. If Pi Day is the International Women’s Day of mathematical appreciation, Britain’s Pie Week, which came to a crusty end on Sunday, is the International Men’s Day that no-one, bar comedians using Twitter as a launchpad for their own wokeness, can name off hand. What a shame, for pie, such a miniature word, is packed full of mystery.

First and foremost, it is exceedingly difficult to nail down the origins of the word. While pi is derived from the first letter of the Greek word perimetros (circumference), pies were etymologically baked in an oven turned to Medieval Latin, either set on pia (pastry) or even pica (magpie). Given that pie is a catchall for a vast array of culinary things, the implication of the word is a mess or mix, which the bling-loving corvids are known for making.

The world loves pie

Mankind’s taste for accommodating foods within a case of pastry or dough permeates through almost all of the world’s food cultures. Pasties, ravioli, empanadas are all somewhere on the Venn diagram of pie, but pale in significance to the golden bales of baked goodness. In their earliest form, form merely followed function, with stewed meats bubbling in their own juices inside a coffin, the medieval name given to the tough pastry form that was typically tossed away once its contents were devoured. Coffin pastry was a hot-water dough, with lard melted and mixed with flour, which finds its modern descendant in the pork pie.

As impressive as pi’s computative dexterity is, pies have also gone in for extremes, their humble origins paving the way to incredible feats of cooking that go so far beyond over-statement it beggars belief; in 17th-century England, the Battalia Pye was stuffed to the brim with “cocks-combs, goose-gibbets, ghizzards, livers, and other appurtencances of fowls,” according to a printed recipe, all packed into a pastry case crimped to look like the crenellated battlements around the egde of a castle tower. A century later and the Yorkshire Christmas Pie became a pie institution, seeing a turkey stuffed with a chicken, itself stuffed with a goose that was bloated to the bill by a duck, a kind of meaty mallard Matryoshka. But such largesse was already being concocted half a millennium earlier in the Arab world, with the traveller Abd el-Latif once working his way through a slice of pie containing three lambs, 90 different birds, and a dollop of pretty much everything imaginable.

Beyond the figures

Pie too has earned its place in spoken and popular culture; you can have a finger in every one, but in such instances it’s important to distinguish between humble and cutie. Talkative sorts of a disagreeable nature should be invited to shut their holes thereof, or failing that, take one filled with billowing clouds of cream straight to the face. Should their grievances continue to mount, follow the Shakespearean method laid out by Titus Andronicus, who baked the sons of Tamora, queen of the Goths, in a pastry coffin.

So this Pi Day, certainly marvel at the mathematical might of formula, but don’t forget to honour a slice of the other one too.