Thirty years ago today, gay and bisexual men in Ireland awoke to the reality that they were no longer criminals.

For generations, the Victorian-era Offences Against The Persons Act had cast a long shadow over their lives; many in Irish society frowned upon extra-marital sex - but it was only a criminal act between two men.

Few LGBT people lived openly and the ones that did were widely regarded with suspicion.

“Once you’re socially ostracised and you’re considered a criminal, so many opportunities shut down to you,” LGBT rights activist Tonie Walsh told Newstalk.

“I’m thinking of a friend of mine who worked for the Department of Justice in the 1980s, although he was openly gay and his gayness was tolerated - he was a very charming individual - it was made clear to him that he would never be considered for promotion.

“That in fact, he was considered a ‘security risk’ by virtue of being a gay man.”

In today’s Ireland that would be illegal - but in the 1980s Mr Walsh considered his friend “one of the lucky ones”.

Anti-discrimination laws were almost unthinkable, and employers were quite within their rights to sack someone they suspected of being LGBT.

“1993 changed everything,” Mr Walsh said.

“When I first came out in 1979, I was 19-years-of-age and I would be refused service in a bar if I looked gay or if the management imagined I was gay.

“That happened on a regular basis.”

'An extraordinary shift'

In 1988, Senator David Norris won a landmark legal case in the European Court of Human Rights.

The Strasbourg judges declared Ireland’s criminalisation of homosexuality breached his human rights and the ruling was binding on the Irish Government.

Despite this, it would be another five years before the legislation was brought before the Oireachtas - something, with hindsight, Senator Norris believes was a blessing.

“The Minister at that time [in 1988] was a man, Ray Burke, who wasn’t the most advanced in his thinking,” Senator Norris said.

“The five year gap meant there was time for a woman to come in, Máire Geoghegan-Quinn, and a Fine Gael activist Phil Moore, who had a gay son Dermot, spoke to Máire Geoghegan-Quinn as one mother to another and I think that was crucial.”

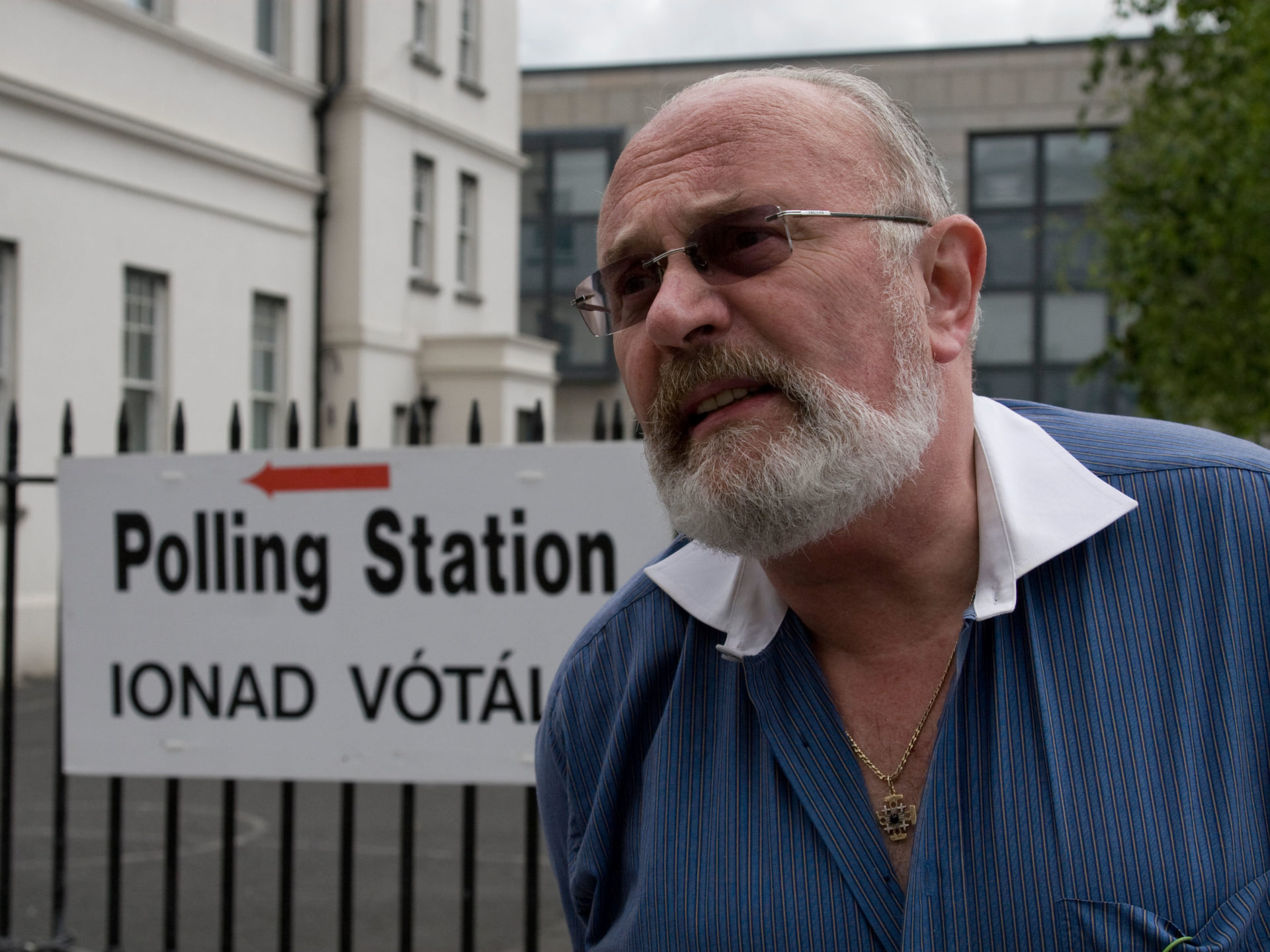

Senator David Norris

Senator David NorrisThe passage of the Criminal Law Bill (Sexual Offences) Bill through the Oireachtas wiped the Offences Against The Persons Act from the statute book.

Ms Geoghegan-Quinn said it was time for the State to stop policing the private lives of Irish citizens.

“How can we reconcile criminal sanctions in this area with the fact there is a whole range of other private consenting behaviour between adults, which may be regarded by many as wrong, but in which the criminal law has no part to play?” she asked TDs.

There were some dissenting voices; Gay Mitchell of Fine Gael said he believed in decriminalisation but that there should be a higher age of consent for homosexual acts “to protect vulnerable people”.

Paul McGrath, also of Fine Gael, said he was worried it sent a worrying message to society.

“Are we now going to see exhibitions in public by homosexuals?” he asked.

“Holding hands, kissing, cuddling et cetera? Is homosexual behaviour to be put on a par with heterosexual behaviour and I think we should reflect that a majority of people in this country would not favour such a move.”

For many gay and bisexual men, 24th June 1993 was a day they will always remember with joy and happiness - but Senator Norris confesses it all left him feeling “flat”.

“There were other people who turned up at Leinster House with a bottle of champagne - including Phil Moore - and they had a nice toast [but] I wasn’t invited,” he recalled.

“They were happy, they were pleased and so on, it was a celebration.”

For Tonie Walsh, decriminalisation meant a weight had been lifted from his shoulders.

“Decriminalisation was not the end point, it was merely the beginning,” he said.

“I think that’s what was so important about 1993; okay, one day we were criminals, the next day we were no longer criminals but [it] signalled an extraordinary shift in the way Irish society viewed its sexual minorities.

“Once we were no longer branded criminals, first of all the corporate sector came rushing to us, embracing us as consumers for better or worse.

“It opened up huge opportunities for social-cultural events, statutory funding of LGBT groups and events that just would have been unthinkable before 1993… So, I look at 1993 as giving a licence to Irish society to finally engage with sexual minorities in its midst.

“There was a liberation of possibility there.”

Disregard

Three decades on and, for many, the hurt and stigmatisation of criminalisation lingers on.

In 2016, Labour Senator Ged Nash proposed a disregard scheme - in which the State would disregard the convictions of those prosecuted under the act.

A disregard is distinct from a pardon as it acknowledges those prosecuted had nothing wrong - but it is legally complex.

“There was a view that elements of legislation required greater consideration,” now Deputy Nash told Newstalk.

“We were, frankly, kicking an open door with then-Minister for Justice Charlie Flanagan - who was very supportive of this process.

“I would single out his advisors and the officials in the Department of Justice who, to be fair to them, engaged very openly with me and my Labour Party colleagues to finesse and nuance the legislation.

“We did decide after a period of months that the best and most inclusive way to design an appropriate and sensitive scheme of disregard was to establish a working group.”

This week, the group published its report and recommended a statutory scheme to enable the disregard of relevant criminal records.

Minister @HMcEntee publishes report on disregarding certain historic convictions related to consensual sexual activity between men

• Scheme will seek to meaningfully address some of the harm caused to affected men and the wider LGBTQI+ populationhttps://t.co/5buNui9VHd pic.twitter.com/6kUBAr7aPy— Department of Justice 🇮🇪 (@DeptJusticeIRL) June 22, 2023

Justice Minister Helen McEntee described it as an “important moment” in the State’s effort to do right by those affected by criminalisation.

“While we cannot undo the hurt inflicted on people who were discriminated against for simply being themselves, I do hope that today’s report brings us closer to something that can address the harm done to generations of gay and bisexual men,” she said.

Thirty years since the Offences Against The Persons Act was consigned to the dustbin of history, the convictions of men prosecuted for loving other men look set to be expunged from the official record.

Main image: The Irish and Rainbow flags. Picture by: Alamy.com