With the news that the Australian government is set to take away welfare benefits from parents who refuse to immunise their children against diseases like measles under the "no jab, no pay" initiative, vaccines are once again a sticking point.

On this evening's The Right Hook, George will be broadcasting live from Notre Dame University, in the heart of Indiana, and will be asking should parents see their benefits stripped if they make the choice not to vaccinate. Joining George in the discussion will be Alf Nicholson, consultant paediatrician in Temple Street Children's University Hospital, Dublin.

Tune in live at 5.30pm or listen back on the podcast here.

Yesterday marked the 60th anniversary of a miracle that changed the lives of millions of people around the world. On April 12th, 1955, Jonas Salk’s inactivated Polio vaccine was declared “safe, effective, and potent,” by the Food & Drug Administration of the United States of America, paving the way for immunisation to take place around the world.

It could not have come at a better time of year, as Polio season usually kicked off at the start of May and carried on through the summer, the disease spreading without warning, striking victims indiscriminately, with no way of telling who would catch it and who would be lucky enough to escape.

Ann Hill of Tallahassee, Florida, receives one of the first ever vaccines in 1954 [Wiki Commons]

Salk started researching Polio in the late 1940s, and developed the first experimental version of it by 1952. The clinical trials into its effectiveness would be the most extensive ever carried out, with more than 5,300 people becoming guinea pigs between May 1952 and March 1954 – including Salk, his wife, and his three sons.

The initial wave proved a success, with no reports of side effects and the successful discovery of Polio-fighting antibodies in blood tests. The second wave would see the vaccine trial massively expanded to almost two million American schoolchildren, referred to in the media as ‘Polio Pioneers’, sampled from all across the nation and entirely funded by thousands of donations from the public.

But some of them had paid a price, as the vaccine’s trial went hand in hand with the worst pharmaceutical disaster in the history of the world, the Cutter Incident. In 1955, reports came in of a number of children presenting with symptoms of Polio in their arms, rather than in their legs, which was more common. The number of children increased over the coming weeks, until it was traced back to bad batch of the vaccine, containing a live viral strain, produced at the Cutter labs in California. Five children died and 56 were paralysed by the jabs, and their infection was linked to the deaths of another five children and the paralysis of 112 others.

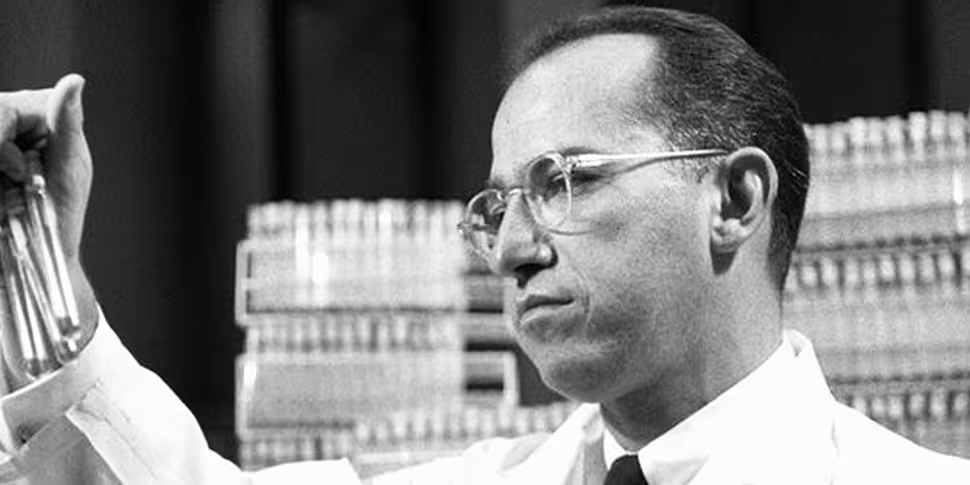

A promotional still for the 'Polio Pioneers' in 1954 [Wiki Commons]

But not even Jonas Salk knew, on that morning 60 years ago, whether or not the trial has been a success. The pressure was enormous, and the palpable fear of Polio waiting to pounce and paralyse at any moment. The vaccine was not entirely to Salk’s specifications, as the US government has insisted at the 11th hour that thimerosal, an antibacterial preservative known as ‘Monkey Blood’ due to its deep red hue, be included in the trial batch. Salk had no choice but to include it, despite having no way of knowing whether or not it would negatively affect the concoctions ability to induce an immune response to the disease.

But the worry was in vain. With only a handful of allergic reactions among the sample, the FDA ruled the vaccine was safe, and it went into mass production later that afternoon. Within six years, the infection rate of Polio had fallen by 96 percent.

Salk’s vaccine, of course, is not the only one, and thousands of Irish people will remember swallowing sugar cubes dosed with the oral vaccine created by Albert Sabin in 1961. Cheaper to produce and administer, that version is still used all over the developing world, although it can result in infection in about one in 750,000 people. And the World Health Organisation and the Global Polio Eradication Initiative are making efforts to push the injection vaccine, and are starting the phasing out process of the oral one.

As such, while we’re now celebrating the anniversary of Salk’s miracle, we’re also one step closer to celebrating its retirement.

Tune in to The Right Hook, every weekday from 4.30pm to 7pm.