A new study has found that asteroids coming towards Earth may be harder to break than scientists previously thought.

The research from Johns Hopkins University in the US used a new understanding of rock fracture, and a new computer modeling method to simulate asteroid collisions.

It said the findings can help in the creation of asteroid impact and deflection strategies, increase understanding of solar system formation and help design asteroid mining efforts.

Charles El Mir is from the Whiting School of Engineering's Department of Mechanical Engineering, and the paper's first author.

He said: "We used to believe that the larger the object, the more easily it would break, because bigger objects are more likely to have flaws.

"Our findings, however, show that asteroids are stronger than we used to think and require more energy to be completely shattered".

Researchers understand physical materials like rocks at a laboratory scale, but it has been difficult to translate this understanding to city-size objects like asteroids.

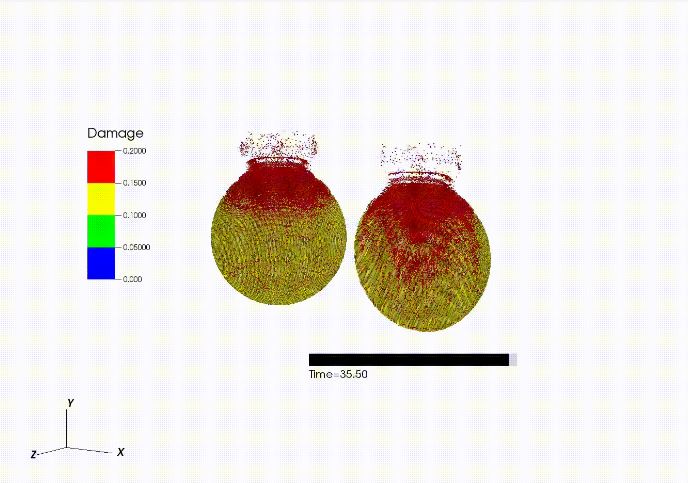

The first phase shows the processes that begin immediately after an asteroid is hit | Image: Charles El Mir

The first phase shows the processes that begin immediately after an asteroid is hit | Image: Charles El MirIn the early 2000s, a different research team created a computer model into which they input various factors such as mass, temperature, and material brittleness, and simulated an asteroid about a kilometre in diameter striking head-on into a 25-kilometre diameter target asteroid.

Their results suggested that the target asteroid would be completely destroyed by the impact.

But in the new study, El Mir and his colleagues entered the same scenario into a new computer model called the Tonge-Ramesh model.

The model accounts for the more detailed, smaller-scale processes that occur during an asteroid collision.

Previous models did not properly account for the limited speed of cracks in the asteroids.

"Our question was, how much energy does it take to actually destroy an asteroid and break it into pieces?", El Mir said.

The simulation was separated into two phases: in the first phase, after the asteroid was hit, millions of cracks formed and rippled throughout the asteroid, parts of the asteroid flowed like sand and a crater was created.

The new model showed that the entire asteroid is not broken by the impact, unlike what was previously thought.

Instead, the impacted asteroid had a large damaged core that then exerted a strong gravitational pull on the fragments in the second phase of the simulation.

The second phase showed the effect gravity had on the pieces that fly off an asteroid’s surface after impact. This phase occurs over many hours.

The findings are set to be published in the March 15th print issue of Icarus.

Main image: An artist's concept shows part of an asteroid breaking off a larger body | Image: NASA