In the decades since astronauts first landed on the moon, a human mission to Mars has been the next great objective for many scientists.

It's a prospect that frequently pops up in science fiction, and in recent years it has been talked up by the likes of NASA and Elon Musk.

NASA, for their part, say they are still planning to send humans to Mars in the future, and recent rover missions to the planet are gathering data for that purpose.

However, this all comes at a time when it has been decades since a manned moon mission, due to the extremely high costs and a plethora of practical issues.

Some private and commercial efforts to make progress on a manned mission to Mars - including the ill-fated Mars One initiative - have come and gone.

Nonetheless, the advent of 'reusable' rockets and the slow move towards commercial space travel are among the developments that started to change the economic and practical outlook of space travel.

Dr Philip Metzger, Planetary Scientist at the Florida Space Institute, told Futureproof he believes a human mission to Mars is likely still 20-30 years away.

However, he believes progress is being made despite the many challenges yet to be overcome.

He said: “I think 20 years is at the beginning of the window where I would expect it to happen. I don’t think we’re going to get there before 20 years - it might actually take 30 years. But I think we are on a trajectory now.

“We’ve got a lot of organisations focused on getting us to Mars. The technology is making dramatic progress, and the cost of spaceflight is coming way down.”

He noted that further trips to the moon will help offer answers to some of the problems - although some solutions, such as the use of solar power, will not work as well for Mars.

The dust problem

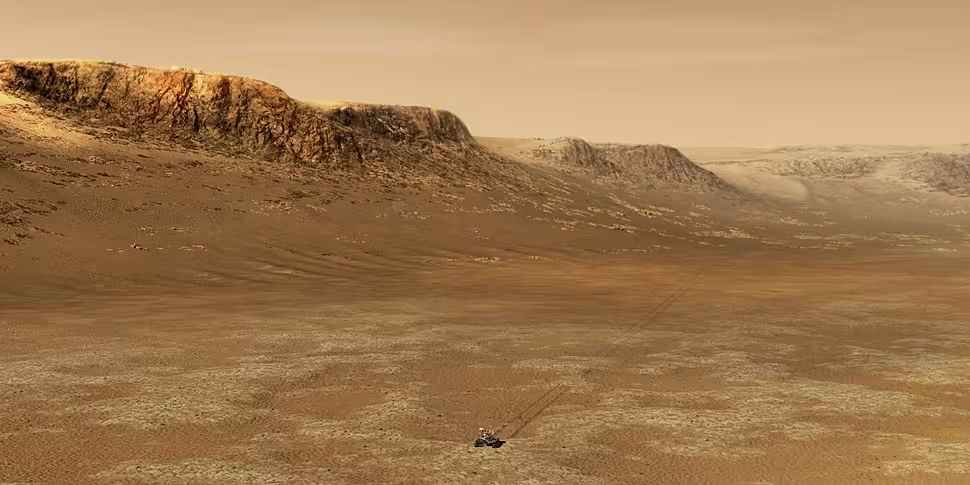

Dr Metzger explained that one of the key problems is the dust and soil present in the Martian landscape and atmosphere.

He said: “Over geological timescales, the dust just accumulated. It’s everywhere… and it’s abrasive, so it gets into your technology.

“It’s not just the dust, but more generally the soil. The landing problem is the rocket exhaust… if you want exhaust large enough to support a large lander in that gravity of that planetary body, then it’s going to be a very effective digger.

“It digs into the ground and it blows the soil and the rocks and the dust everywhere. They get up to very high velocity and then can hit the bottom of your rocket or your outpost.

"It can also dig a deep hole - when that hole starts to cave in after you’re turned off your rocket engines, it can cause some tilting in the lander - which could be unacceptable or hazardous to the mission."

Work is underway on around 50 different technologies to try to solve this particular problem.

However, Dr Metzger believes “decades of work” still lie ahead to make an effective landing pad - including the development needed so a lot of the necessary work can happen autonomously or remotely.

He said: “It’s going to take a series of missions to develop the technology, and then finally one last mission to build that landing pad.”

Work is also underway on ways to land without a landing pad, although Dr Metzger believes scientists and technicians won’t be able to get to that point.

He said: “In the end, I think we’re going to end up doing landing pads.

"But right now I think they haven’t completely focused on landing pads, as they’re keeping the hope alive for the alternative approach.”