Seventy-five years ago today, Ireland officially became a Republic and left the Commonwealth of Nations.

Thirty-three years after Patrick Pearse stood outside the GPO and read out the Proclamation of the Irish Republic, the 26 counties’ last link with the British monarchy had been cut.

The Sunday Independent noted April 18th, 1949, was a day marked with "nationwide rejoicing, with all the pomp and pageantry the country can muster".

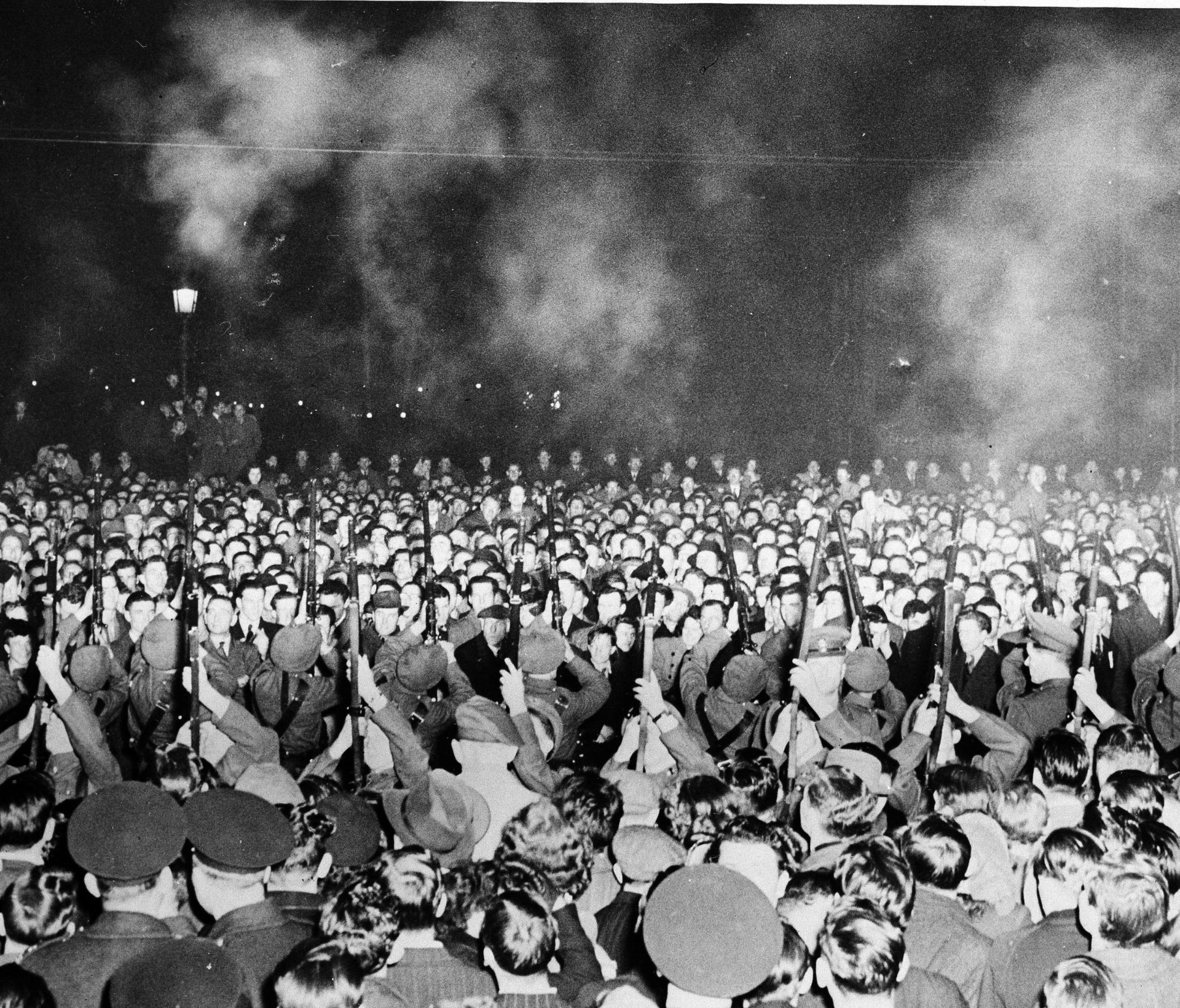

In Dublin, fireworks exploded in the night sky above thousands of happy revellers, complemented with a gun carriage salute from the Defence Forces.

Celebrations in Dublin as Ireland left the Commonwealth. (AP Photo)

Celebrations in Dublin as Ireland left the Commonwealth. (AP Photo)Years later, Newstalk listeners voted it the greatest moment in Irish history - but not everyone was happy.

Even today, in the Monaghan village of Drum, where most locals are Protestant, many still feel a sense of attachment to the British monarchy.

“Even this area has changed,” local man David Stewart told Newstalk.

“We should expect that being a minority but there is still that lingering loyalty to the Crown from many folk around here.

“For example, we had a service up in one of the local Churches for the passing of Queen Elizabeth.”

An historic connection

Prior to partition, Drum was a stronghold of unionism and the ancestors of many locals signed the Ulster Covenant, urging the British Government to exempt their province from Home Rule.

After partition, many felt bitterly betrayed but their love for the United Kingdom and the British monarchy endured.

The Stewart family home might be in County Monaghan but they still identify as British - and act accordingly.

Every Christmas Day at 3pm, the King’s Christmas message is switched on and the family stand respectfully when the British National Anthem is played.

“You can see among Dad’s stuff, there’s a plate behind us there, that’s uncle Fred’s and it’s of King George,” Mr Stewart said.

“You would find that throughout this area, loads of stuff like that in people’s houses where the monarchy was very much at the heart of people’s culture and mindset.”

Despite this, Mr Stewart admits attitudes towards the new King Charles are tepid and, like many Britons, he misses Queen Elizabeth.

“There’s not the same warmth to Charles,” he said.

“I think that’s because there was something special about the Queen.

“Although, we would still recognise Charles as King; I would render unto Caesar what’s due to Caesar.

“He is my King and I have respect for him.”

'The end of an era'

Journalist and author Mary Kenny was five-years-old in 1949 but has vivid memories of the day Ireland became a Republic.

“My brother James brought me to the Dodder River, which looked over towards Ringsend,” she said.

“There was a huge fireworks display which was celebrating the declaration of the Republic and it seemed absolutely wonderful to me as a child.

“I was a bit confused in some way because I thought, with some reason, that the Republic had been declared in 1916.

“Then I came to understand that Éire was leaving the Commonwealth of British Nations and declaring a full Republic - something that did become quite controversial.”

Irish troops parade in O'Connell Street celebrating the birth of the Irish Republic on April 18, 1949. (AP Photo)

Irish troops parade in O'Connell Street celebrating the birth of the Irish Republic on April 18, 1949. (AP Photo)When Ireland became independent in 1922, the new Free State had reluctantly become a member of the Commonwealth of Nations.

It meant the British monarch remained Ireland’s head of state - a fact that led many disgusted TDs to oppose the Anglo-Irish Treaty.

In 1937, a new Constitution had been drawn up that contained no reference whatsoever to the Crown and Winston Churchill described Ireland as “neither in nor out” of the Commonwealth.

Confusingly though, the External Relations (Executive Authority) Act of 1936 had empowered the British monarch to sign letters of credence for Irish diplomats.

In all other aspects, power and authority rested completely with the Oireachtas.

The final break was announced in 1948, when Taoiseach John A. Costello announced Ireland would leave the Commonwealth and officially declare itself a republic.

Decades on, Fine Gael considers the decision one of its greatest achievements in office.

“It had been said by Michael Collins and others, Kevin O’Higgins, around the time of the Civil War and the early years of our State that the Free State was a stepping stone,” Fine Gael TD Charlie Flanagan told Newstalk.

“Certainly, the completion [of that stepping stone] was the declaration of the Republic and interestingly enough, in order to ensure there was a Fine Gael stamp on it, when Costello took the bill through the Dáil towards enactment, he took it as Taoiseach - which was unusual.

“It wasn’t left to the line Minister at the time, which would have been Seán McBride, who at the time was Minister for External Affairs.”

King George VI and his family.

King George VI and his family.However, the decision upset some Fine Gael supporters from the Protestant community, many of whom valued the connection Commonwealth membership provided with Britain and other English-speaking countries around the world.

While researching her book, Crown and Shamrock: Love and Hate Between Ireland and the British Monarchy, Mary Kenny found a number of Irish people had written to King George, expressing their distress at the constitutional change.

“Mrs Dorris Weir, who attended the Church of Ireland in Irishtown, wrote to the King to say it was like a farewell and she was really sorry they wouldn’t pray for the King anymore in the Church of Ireland,” Ms Kenny said.

“They would now be obliged to pray for the President and they would no longer be allowed to sing God Save The King - which they had done.

“She wrote to say she would still maintain feelings of love towards this institution and the King did send a nice letter.

“It was kind of the end of an era for Irish Protestants of the time.”

'Part of a discussion'

Not long after Ireland left the Commonwealth, India indicated it wished to become a republic while remaining a member of the organisation.

The London Declaration of 1949 announced a compromise; member states could abolish the monarchy but remain part of the Commonwealth if they recognised the British monarch as “the symbol of the free association of its independent member nations and as such the Head of the Commonwealth.”

Ireland decided not to re-apply for membership but Deputy Flanagan feels it is conversation worth having in the event of a border poll.

“I think there was a reluctance on the part of the Irish people to [rejoin] what was then the British Commonwealth,” he said.

“We had fought hard for our independence, we had spilt blood for our independence.

“So, I’m not sure if there were circumstances under which, in the 1950s, we would have re-joined the British Commonwealth.

“However, 70 years later circumstances have changed; it’s no longer the British Commonwealth and it’s mainly a body that engages in trade, sport and culture.

“I still don’t believe that the majority of the Irish people, if asked, would support the rejoining of the Commonwealth but I do think it’s something that obviously will have to be part of a discussion should there be, at some stage in the future, a united Ireland.”

A British flag flies next to an Irish Tricolour at Government Buildings in Dublin. Picture by: Brian O'Leary/RollingNews.ie

A British flag flies next to an Irish Tricolour at Government Buildings in Dublin. Picture by: Brian O'Leary/RollingNews.ieAs Prince of Wales, King Charles visited the Republic of Ireland a number of times on behalf of the British Government.

On one such occasion, he told Deputy Flanagan he hoped to travel to all 32 counties on the island.

Could his next visit include a stop in Drum? David Stewart and his father, William, chuckled at the suggestion.

“Well, we wouldn’t kick him out,” William laughed.

“But I can’t see that happening.”

Main image: David and William Stewart with a plate with King George on it. April 2024. Image: Newstalk