The thing to remember first about Mary Robinson’s presidency, arguably the most important election to ever happen to a role most considered a retirement home for the Fianna Fáil faithful, is that when she first agreed to run under the Labour ticket - albeit as an independent - she didn’t even necessarily want to win. Robinson wanted to set an agenda, to embarrass the political status quo of Ireland into realising that being the head of the Irish State was a honour, a duty, and a job.

Her political career had always been about embarrassing the right-leaning centrist governments of the day, taking a staunchly liberal stance to the democratic dogma of Irish party politics. Whether contraception, divorce, the status of homosexuals, travellers' rights, women's rights, or the destruction of Wood Quay, she would toss iconoclastic grenades at cabinets and ministers, or lead the debate on issues in referendums , always on the right side of history but, more often than not, the wrong side of the day.

The daughter of wealthy Mayo doctors, she has been a boarder in Dublin, gone to finishing school in Paris, read Law at Trinity and Harvard, and passed through the Honorable Society of King’s Inns, delivering poised and searingly astute legal opinions throughout her career at the bar. She was a lecturer on constitutional and criminal law, and the youngest woman ever elected to the Seanad - granted, as one of the three stuffy academics Trinity College got to send to the upper house of the Oireachtas, but a buck-trending Catholic one. By the time Dick Spring, Labour leader, approached her in early 1990, she had joined Labour, twice failed to be elected to the Dáil, had left Labour due to her disagreement with the Anglo-Irish Agreement, and had abandoned the Senate after 20 years tailoring the legislation of the state. In fact, when Dick Spring arrived with the offer to support her run for the Áras, she didn’t even realise what he was suggesting.

Robinson had thought that Spring was merely asking her, as an expert of Irish constitutional law, to offer an academic stance on what exactly the role of the President of Ireland, Uachtaráin na hÉireann, might be.

How strange she must have felt, standing around Dublin’s RDS during the count as the vote tallies came in. She didn’t win on first preference, with Brian Lenihan Snr, despite scandals of “mature recollection” forcing him to resign as the Tánaiste just weeks before polling day, still edging ahead in the popular vote. Old habits die hard. But when Austin Currie, a Northern Irish civil-rights activist and the Fine Gael nominee was ruled out, a transfer agreement and the overwhelming support of Irish women carried Robinson comfortably over the line.

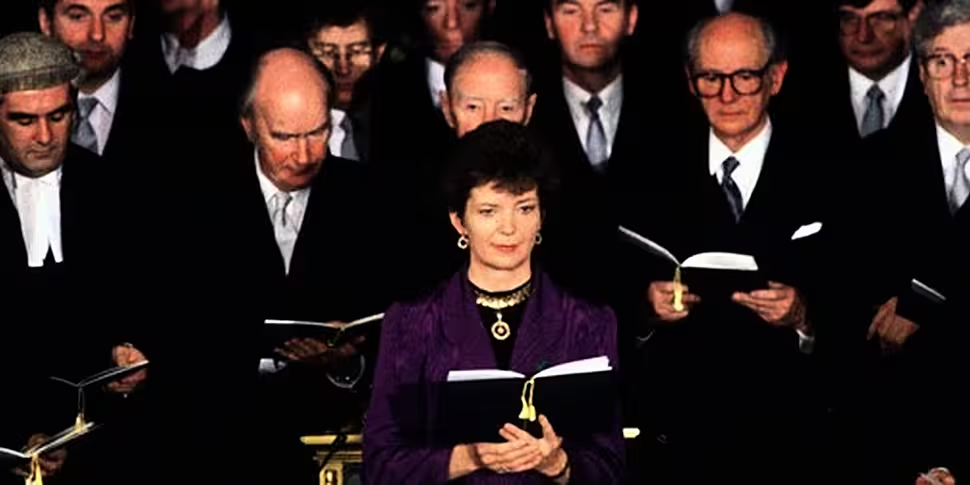

Mary Robinson at the count centre in the RDS in Dublin at the moment it became clear she had won the presidential election on November 9th, 1990 [Eamonn Farrell/RollingNews.ie]

There she stood, tall and always looking a little bit awkward, having worked for months to change her image as a chilly, ivory-towered academic. The campaign had seen her dedication to motherhood and family life described as a “newfound” electoral gimmick by a cabinet minister on national radio, and she was now shorn of her pudding-bowl haircut and dressed in softer, more feminine - but still business-like - clothes. There she stood, surrounded by a Taoiseach that didn’t want her to win and the false smiles of the political establishment, ready to speak into a microphone and address the nation she now represented with a speech so good, RTÉ broadcast it instead of the Angelus.

“I must be a President for all the people, but more than that, I want to be a President for all the people. Because I was elected by men and women of all parties and none, by many with great moral courage, who stepped out from the faded flags of the Civil War and voted for a new Ireland, and above all by the women of Ireland, mná na hÉireann, who instead of rocking the cradle, rocked the system. And who came out massively to make their mark on the ballot paper and on a new Ireland.”

When she announced, a little more than six years later, that she would not be running for a second term of office, the general opinion was that Robinson had revitalised the Irish presidency, sidestepping the political whims of various taoisigh, opening her role to the Irish diaspora, and carrying out some controversial and ground-breaking firsts. The critics, who had lined up to rip her to shreds on the campaign trail were quickly silenced, and more often than not won over to her cause, as she showed, with grace and eloquence, the substance in the role of head of state.

As a champion of human rights, she met the Dalai Lama, despite criticism from the Chinese government and repeated suggestions from Charles Haughey that she should not. She went to London and became the first Irish President to meet Queen Elizabeth, and welcomed Prince Charles to her home in Dublin. These trips might well seem like formulaic meetings now, but they were, at the time, recognised as hugely significant in the development of a forward-looking Republic and a pluralistic Ireland.

In Belfast she shook Gerry Adams’ hand, drawing criticism from the pundits and politicians, and staunchly, but rationally, defending her move at a press conference, saying he was elected by the people of West Belfast, and in shaking his hand, she was shaking theirs.

President Mary Robinson with the Queen Elizabeth of England outside Buckingham Palace London in May, 1993 [Eamonn Farrell/RollingNews.ie]

The moments that best, perhaps, define her all encompassing humanity came during state visits to Africa, where she did the Irish proud by becoming one of the first world leaders to highlight the horrors of hunger and genocide in Somalia and Rwanda. On the evening news, the Irish people, who for decades were used to watching her issue concise and clever rhetoric, always delivered with unassailable calmness, were humbled to see Robinson - to see Mary - shaken to her core, her political mask slipping away as she recounted what she had witnessed.

“It has been a very difficult three days,” she said, her voice giving away the raw emotion she could barely suppress. “Very, very difficult. I found that when I was there, in Baidoa, and in Afgoye, and in Mogadishu, and this morning in Mandera, that I had no difficulty in remaining calm and in not letting my emotions show. And I’m… em… sorry that I cannot be entirely calm speaking to you, because I have such a sense of what the world must take responsibility for.”

It is powerful viewing, honest and ashamed, agonising the world’s communities towards atoning for their sins, for turning a blind eye to mindless violence, suffering, desperation, and anguish.

In reminding the world to look, the world took notice of her. Robinson left the Irish presidency before the end of her term, which many people regard as a political gaffe. Others call it a slight. She left to take on the cause of human rights at the United Nations, buoyed on by the reputation of her integrity and the significance of her office, the one to which the people of Ireland elected her. We set the stage, she stole the show. That her work as Irish President helped her become one of the foremost authorities on human rights in the world is something that should be of immense pride to everyone in this country.

She served as a figurehead for Irish society, and shook the presidential office into modernity, to the point that the election to name her successor was dominated by female candidates. At a time when our parties are forced to implement gender quotas in order to address the lack of women in politics, Robinson stands as a stark reminder that when the women of Ireland, mná na hÉireann, find their voices, be they quivering or not, the entire country sits up and listens.

When Mary Robinson took to the stage in Dublin Castle at her inauguration ceremony on December 3rd, 1990, dressed in purple silk among a sea of black suits, she finished her speech with a quote from WB Yeats.

“I am of Ireland… Come dance with me in Ireland.”

We’re still dancing.