A group of mice taking part in a NASA study on the International Space Station have surprised scientists by turning their weightlessness into a game.

The study observed the mice as they accustomed themselves to the micro-gravity environment on the space station and recorded changes in their behaviours.

The experiment aimed to increase our understanding of how basic biology works in space - with the results expected to help NASA prepare human astronauts for long-duration missions.

NASA said the 37 days the mice spent in the ISS cage - nicknamed the 'Rodent Hardware System' - would equal a long-duration mission on the scale of the rodent life span.

Microgravity

The mice did all the things they normally would while in microgravity - quickly adapting to their newfound weightlessness by anchoring themselves to the cage with their hindlimbs or tails.

They spent their entire mission exploring the entire habitat and, at the end of the study, they weighed about the same as a group of rodents kept in similar circumstances as a control group back on Earth.

Their coats were also found to be in excellent condition.

NASA said both findings suggest the mice remained in good health.

The mice are launched into orbit on-board a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket, 05-12-2018. Image: SpaceX

The mice are launched into orbit on-board a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket, 05-12-2018. Image: SpaceX"Race tracking"

The space mice were also more active than their counterparts back on Earth and about a week after launch, they began displaying a new "unique behaviour," which scientists dubbed "race tracking."

Often acting in groups, the mice began running laps around the walls of the cage - turning the entire enclosure into a sort of orbital hamster when wheel.

While the images seem to suggest that the rodents are enjoying their surroundings, NASA said there could be a number of explanations for the behaviour.

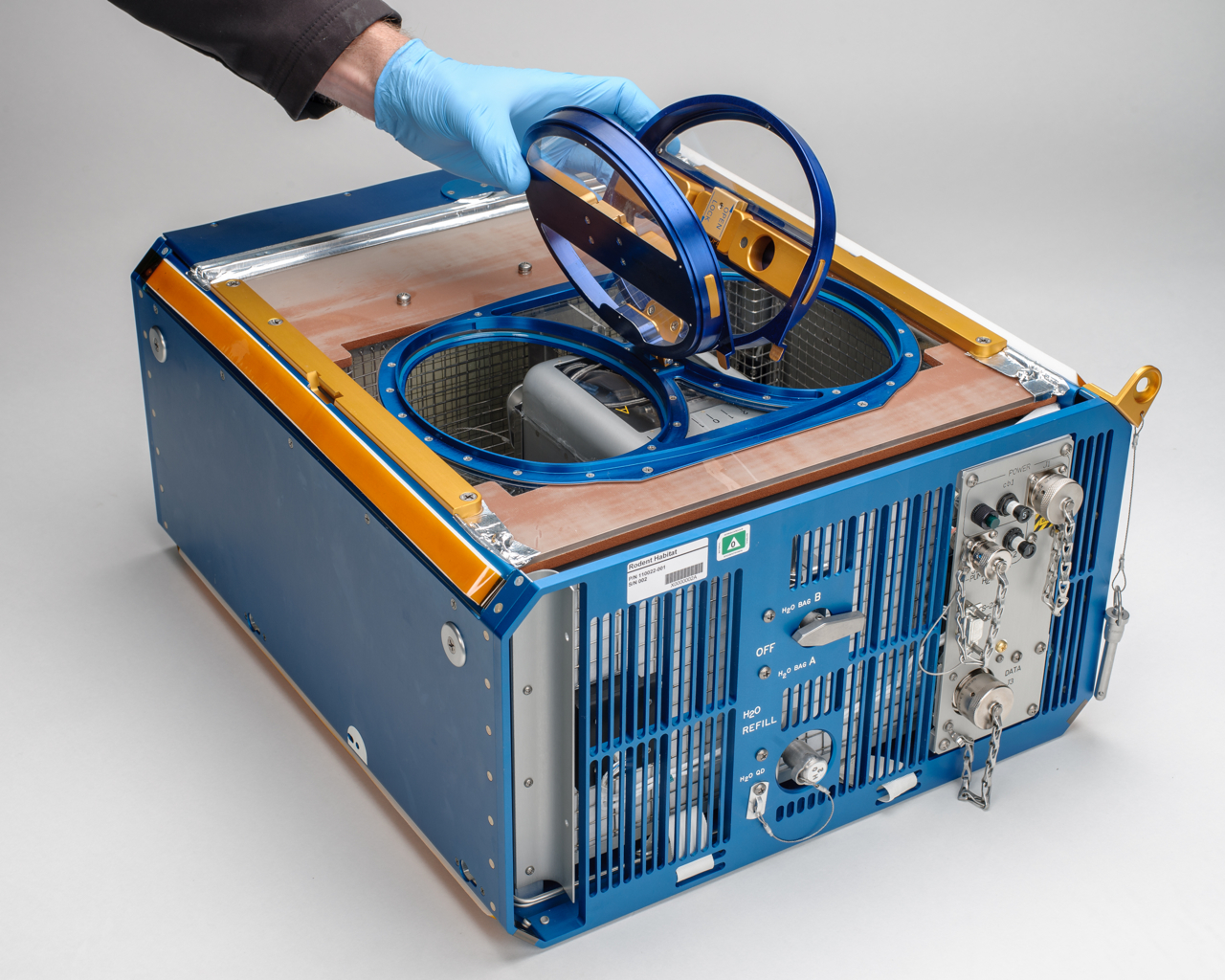

NASA’s Rodent Habitat module with both access doors open. Image: NASA/Dominic Hart

NASA’s Rodent Habitat module with both access doors open. Image: NASA/Dominic HartIt could be that the physical exercise was in itself a reward for the mice or it could be the motion helped with the body's balance system - which is mostly absent in microgravity.

It could also have been a stress response - however, the researchers believe this is less likely as they were in excellent health otherwise.

"Behaviour is a remarkable representation of the biology of the whole organism," said NASA researcher April Ronca. "It informs us about overall health and brain function."

Space mice

NASA said just being aware of the circling behaviour will be helpful for future studies of mouse physiology in space.

The physical activity is also important in terms of studying the effect of microgravity on bone loss - an important consideration for future human space-flight missions.