Mary Manning explains how refusing to process the sale of two South African grapefruits led to a three-year anti-Apartheid strike.

Ms Manning was just 21 when she was asked by her union to boycott South African goods in support of Nelson Mandela and other anti-Apartheid activists in 1984.

“At the time, we didn’t really know anything about what was happening in South Africa,” she told The Pat Kenny Show. “We didn't know about apartheid.”

Still, Ms Manning and other union workers in the Henry Street Dunnes Stores noted all South African products and refused to sell them.

Suspension

Dunnes management began to take notice of the boycott, and eventually Ms Manning was caught in the act.

“A woman was coming towards with me two South African grapefruits and I just said to her, ‘I’m sorry, I can’t, it’s union policy’,” she said.

“She was fine, but the manager who was standing behind me closed my register off and brought me up to the office with Karen [Gearon, who was also boycotting]."

Management gave Ms Manning five minutes to reconsider her boycott. When she refused, she was suspended “indefinitely”.

Strike

Following their suspension, Ms Manning and 10 others began their strike outside the store, discouraging people from shopping.

"It was a beautiful sunny day in July," she said. "We thought we'd just get outside for a couple of days."

The Dunnes Stores strikes began in July 1984 and lasted until April 1987.

Ms Manning said it was from the picket line that she understood the importance of their strike.

“We had people like Nimrod Sejake who was exiled from South Africa and started to talk to us about what was happening in South Africa,” she said.

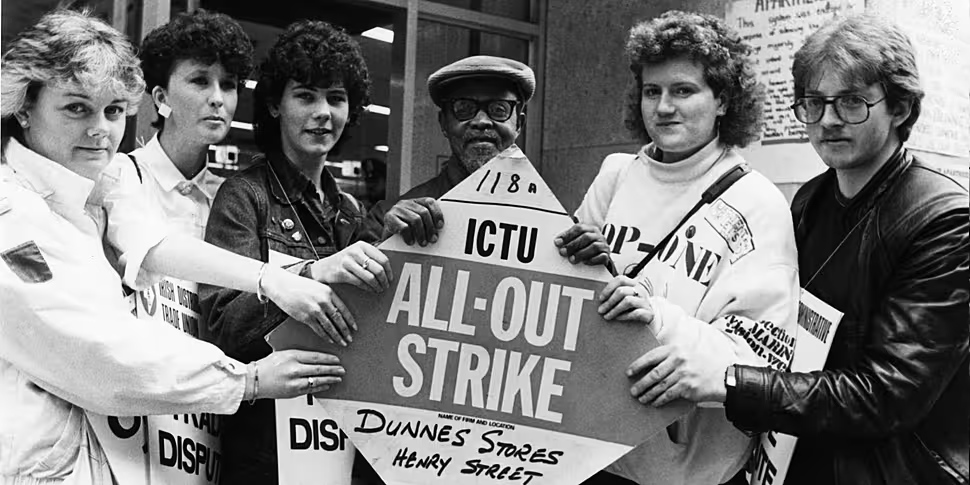

Mary Manning on strike outside Dunnes on Henry Street. 1/8/1984 Photo: RollingNews.ie

Mary Manning on strike outside Dunnes on Henry Street. 1/8/1984 Photo: RollingNews.ie“It became more than a [union] policy, it wasn’t a piece of paper anymore. We were doing it for people who we thought we can show solidarity with.”

The Dunnes Stores strikers were initially criticised by both the Catholic Church and by people who said they were only hurting South African businesses – until they met Bishop Desmond Tutu in December 1984.

“He asked Karen and myself over to London [when he received the Nobel Prize],” Ms Manning explained. “That was one of the big turning points of the strike.

“People started to think, ‘Here’s a man; he’s Black and South African and supports the strikers’.”

Ms Manning and the strikers received more attention when they were invited to South Africa – and quickly deported before they could even leave the airport.

“We had heard so many stories of people dying in custody over there,” she said. “We were very young - I just turned 22. It was actually my birthday on the day we went over.”

'It makes you feel vindicated'

Eventually, the Irish Government put a ban on South African goods, which Nelson Mandela said played a significant role in bringing down Apartheid when he received the Freedom of Dublin in 1990.

Dublin's Deputy Lord Mayor Anne Carter, Dr Kader Asmal and former Dunnes worker Mary Manning kneel next to a plaque commemorating a the anti-Apartheid Strike, 18/06/2008 Image: PA Images / Alamy Stock Photo

Dublin's Deputy Lord Mayor Anne Carter, Dr Kader Asmal and former Dunnes worker Mary Manning kneel next to a plaque commemorating a the anti-Apartheid Strike, 18/06/2008 Image: PA Images / Alamy Stock Photo“I'd actually moved to Australia [by 1990] because I couldn't get a job after the strike finished, and the rest of the strikers met him,” Ms Manning said.

One listener texted in to say she had travelled to Robben Island, where a pilot said he wished he could thank Ms Manning for her work.

“It’s emotional to hear that because," Ms Maning said. "It does make you feel vindicated for what you did, because during the strikes we didn’t.”