At 109-years-of-age, Máirín Hughes is the oldest person in Ireland - but to see her you wouldn’t think so.

At this point, she is one of a handful of living witnesses who can remember clearly the historic and bloody years that freed Ireland from British rule.

Máirín can still recall young lads leaving Ireland to fight in the First World War, the brutality of the War of Independence and the wild euphoria when the British left for the final time.

On a gloriously sunny afternoon, I find her sitting in a chair outside her nursing home in Chapelizod, Dublin, diligently completing the Irish Times sudoku.

She has a head of thick, wavy hair that many men would pay thousands to Turkish doctors for and after I send a picture of us to a friend he replies, “She doesn’t look a day over 75.”

She greets me with a “Go raibh maith agat” for the flowers I have bought her and staff bring us cherries to toast her sailing past yet another milestone birthday.

“Bas in Érinn [death in Ireland],” she says cheerily as the glasses chink together.

Doubtless she will get her wish someday but chatting to her, it seems unlikely I’ll be reading her obituary any time soon.

Hearing aids and a Zimmer frame are the main concessions to her impressive age but mentally she is sharp and she says 109 feels “no different than 100 - except for the fuss that’s been made.”

Born in Belfast, just a few weeks before Europe plunged itself into the First World War, Máirín grew up in Killarney.

Across the Irish Sea, thousands of Irish men were serving in the trenches and she remembers the young Kerry men, dressed smartly in khaki uniforms, as they were driven away to fight and die in the mud of France and Belgium.

“The house that we were living in, it had a sloping lawn down to the road,” she recalls.

“And I’d see the lorries passing through with the British military.”

'It's a Long Way to Tipperary', Irish troops at Gallipoli, Turkey, World War I, c1915-c1916. Artist: Unknown

'It's a Long Way to Tipperary', Irish troops at Gallipoli, Turkey, World War I, c1915-c1916. Artist: UnknownAlmost as soon as the guns fell silent on the Western Front, the War of Independence began as the IRA fought to expel the British from Ireland.

Concerned for the safety of their young family, Máirin’s parents moved them out of Killarney.

“We had to stay in a hotel for about two years,” she recalls.

“Because Mammy and Daddy wanted a house outside the town - not in the middle - on account of all the uproar.”

Still, there is only so much a parent can do to shield their children from the ‘uproar’ of a revolutionary war and Máirín remembers hearing of a Black and Tan ambush in the local area.

“The lorry was going around and one lad had his rifle and he kept shooting,” she says.

“He shot two people because they were digging potatoes.”

Although she remembers the terror of that time, she also recalls the euphoria of perhaps the most important event in the history of Ireland - the day the British left for good.

“One thing I do remember about it is that the British authorities left the barracks that they were in in Killarney and there was wild [rejoicing], cheers and hurrahs up and down the street - things like that.”

A Black and Tan constabulary member in Dublin, smoking and carrying a Lewis gun, February 1921

A Black and Tan constabulary member in Dublin, smoking and carrying a Lewis gun, February 1921It was, even by the standards of the 20th century, a tumultuous childhood but Máirín was cushioned from hardship by the love and affection of two devoted parents. They had met in London’s Hyde Park where the Gaelic League organised regular walks for diaspora Gaeilgeoirí.

“We never wanted for anything,” she says fondly.

“Daddy was a customs and excise officer and my mother was a great provider.

“She helped an awful lot of people [during the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918 and 1919]; I remember standing at the gate of a cottage while she went in with her mask and her food.

“I wouldn’t be let in because of the fever… Looking back, my mother did an amount of good during [those years] when people had hardship and suffering.”

Unusually for a woman of her age, Máirín left school and went on to study Science at University College Cork - specialising in chemistry.

After she graduated, she spent several years helping a professor with his research and served as a fire watcher during the Second World War - donning a tin hat as dusk fell to keep an eye out for Nazi bombers in the skies above.

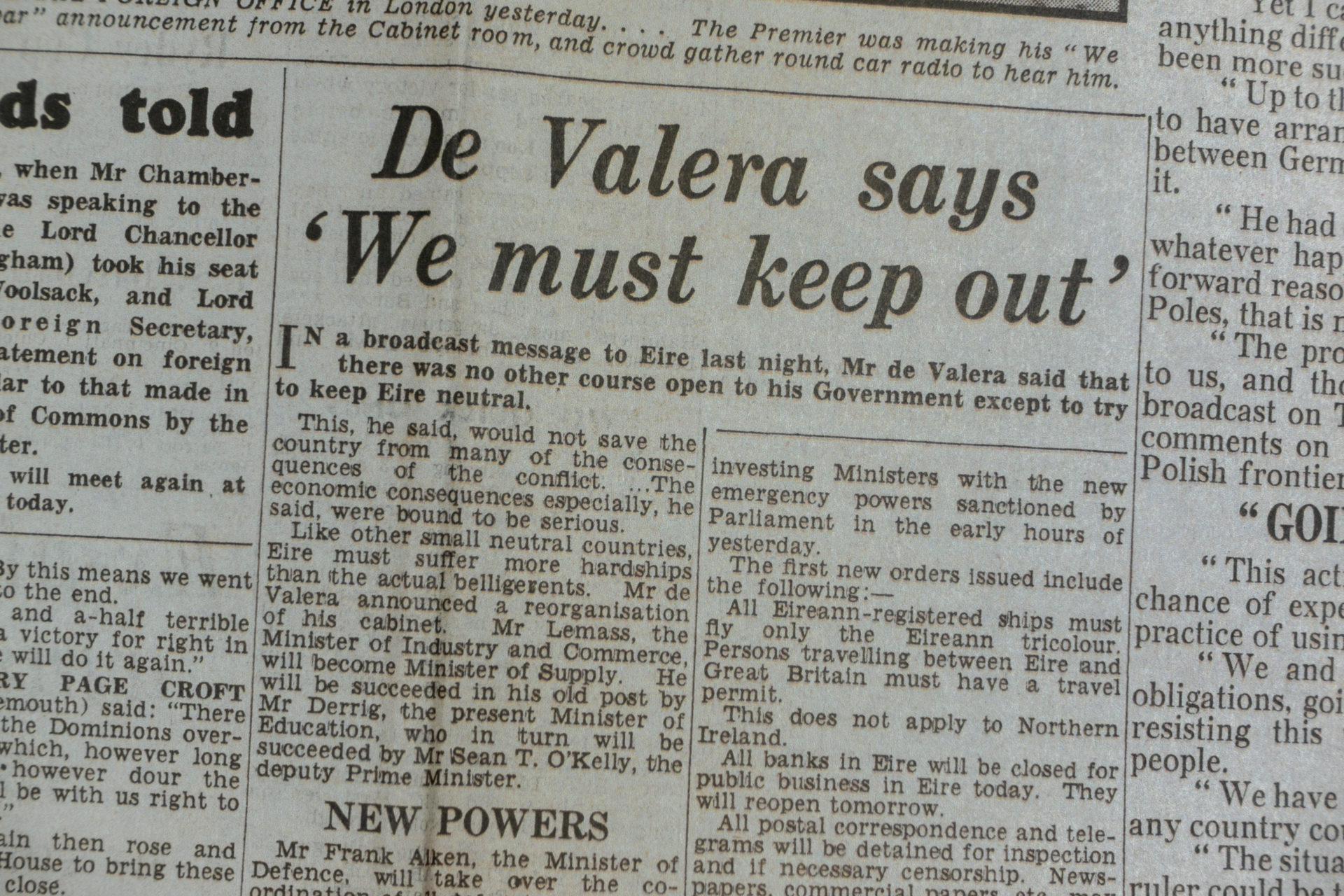

"De Valera says We must keep out" about Irish neutrality in The Daily Express (replica), 4th September 1939, the day after World War II was declared.

"De Valera says We must keep out" about Irish neutrality in The Daily Express (replica), 4th September 1939, the day after World War II was declared.It was love that brought her to Dublin.

“I was working in Cork until I got married,” she says.

“My husband [was] in [the State transport agency] CIÉ, so I had to move up with him then to Palmerstown. That was our first house.”

Her husband Frank was a Sligo man who worked at Heuston Station for Córas Iompair Éireann.

As a good Gaeilgeoir, Máirín pronounces ‘CIÉ’ the correct Irish way and the untrained ear would be forgiven for thinking her husband worked as an American spy for the CIA - stranger things have surely happened in her 11 decades of life.

Dublin city centre in the 1950s.

Dublin city centre in the 1950s.It was in the capital, just a short walk from the Maryfield Nursing Home where she now lives, that Máirín had one of the most memorable experiences of her life.

September 1979 saw the first Papal visit to Ireland’s shores and it marked the giddy zenith of the nation’s love affair with the Catholic Church.

Over a million Irish people turned out to hear John Paul II say Mass in Phoenix Park and, in amongst the faithful, were Máirín and her family.

Pope John Paul II during his visit to Ireland in September 1979. Anwar Hussein/allactiondigital.com

Pope John Paul II during his visit to Ireland in September 1979. Anwar Hussein/allactiondigital.com“I consider the Pope’s visit to Ireland to be outstanding,” she says proudly.

“I was so happy to actually be there with it.

“My mother was with me, we were in the Phoenix Park and we got up early in the morning and every bed in our house was full.

“They’d all come up from the country.

“There was great excitement.”

In 2017, Máirín moved into the Maryfield Nursing Home full time and the affection the staff have for their local celebrity is clear - a sentiment she clearly reciprocates.

“I must say, it’s very comfortable,” she says.

“The staff are exceptional; they’re not staff, they’re friends.

“There’s that attitude about it.

“I’m very happy here; I have no responsibilities.”

After a rendition Oró Sé Do Bheatha 'Bhaile, which she says has always been her favourite song, I bid her farewell.

In the not too distance future, there will be not a soul on the earth who remembers the Great War or when the British left Ireland. Children will learn about those events in schoolbooks and people will watch documentaries about them on the TV.

But nothing can compare to a chat with someone who lived through those times and I'll always remember my afternoon with Máirín, a woman who lived through the most transformative years in Ireland's history.

Main image: Máirín Hughes.