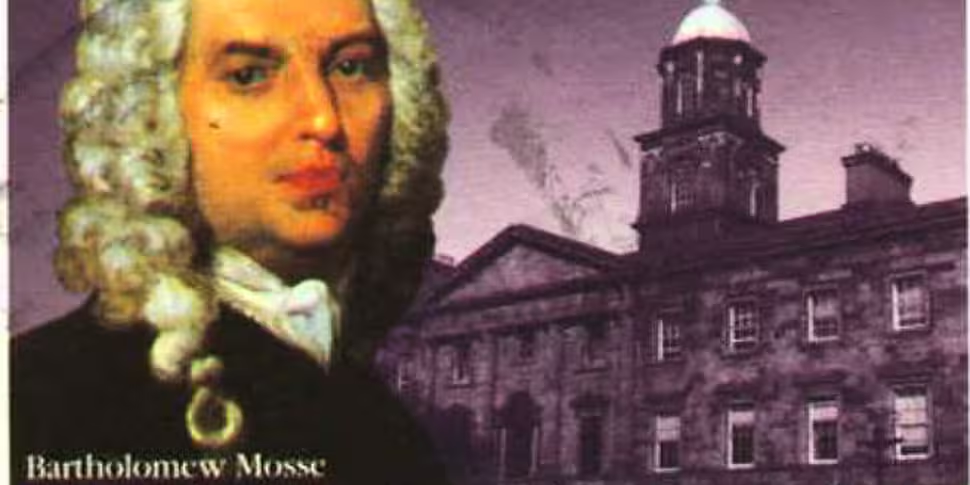

Today's Hidden Histories installment is the turn of the man who is responsible for the birth of a million babies. Dr. Bartholomew Mosse turned a personal tragedy into the motivation behind becoming the founder of the original Dublin Lying-In Hospital, or the Rotunda as we know it today as a maternity training hospital; the first of its kind.

Listen to the podcast here:

For a brief moment on the evening of 13 April 1742, there was silence in the music hall on Dublin’s Fishamble Street. And then the applause began. The clapping and cheers continued long into the night. George Frideric Handel bowed and bowed again. The German-born composer had just conducted the premiere of his sacred oratorio, Messiah. His audience was comprised of the very wealthiest citizens of Ireland, country aristocrats and Dublin merchants alike. Every last one of them knew in their hearts that they had just witnessed one of the most magnificent musical creations in world history.

Amongst those lucky souls was a young surgeon called Bartholomew Mosse. He had been bidden to the event by his friend and mentor, Dr John Stone, a director of Mercer’s Charitable Hospital which co-hosted the evening. As the rousing Hallelujahs and solemn arias of Handel’s Messiah echoed through Fishamble Street that night, 30-year-old Dr Mosse must have considered the elated faces of the prosperous audience and started to day-dream.

Dr Mosse was one of 18th century Ireland’s most remarkable characters. His principle legacy was Dublin’s Rotunda Hospital, the first purpose-built maternity hospital in the world. A man of exceptional compassion, he had an immense gift for fund-raising and may be considered a pioneer of corporate entertainment.

He was born in Portlaoise (then Maryborough) in 1712. His father, the Rev Thomas Mosse, came to Ireland as a chaplain to William III during the Boyne campaign and had been Rector of Maryborough ever since. Young Bartholomew, the sixth child, was given a ‘genteel education’ by a tutor at home.

In 1729, the 17-year-old departed for Jonathan Swift’s Dublin where he became apprenticed to Dr Stone. Mosse proved such an exceptional student that he was given his own licence to practice in 1733. Over the course of the 1730s, Mosse watched with considerable interest as Dr Stone and his friends set about raising funds for the Mercer Hospital. The benefit concerts by the likes of Handel struck him as particularly effective.

From an early age, Dr Mosse wanted to make his mark on Dublin. It was his dream that the city would have its own maternity hospital, an institution where babies would be safely delivered and where other surgeons could be trained in the art of midwifery. Few people in Ireland had any training in Midwifery at this time. The practice was frowned upon by the Royal College of Physicians. But Mosse was determined this was his calling in life.

His motive was personal. In 1737, Dr Mosse was subjected to a dreadful tragedy. His young wife, whom he loved, died giving birth to a small boy who also perished.

In a state of considerable shock, the young surgeon had sought relief in foreign lands, serving as doctor to the British garrison stationed on the Mediterranean island of Minorca.

On his return from Minorca, Mosse visited several hospitals in England, Holland and France, most notably the ‘La Charite’ in Paris, noted for its expertise in midwifery.

In 1742, shortly after he witnessed Handel’s Messiah, he obtained a Licentiate of Midwifery and ‘quit the practice of surgery’.

The conditions in which the poor women of Dublin gave birth at this time were quite shocking. Following the brutal potato famine of 1739, the city had been swamped with destitute refugees from the countryside. Their houses were damp, cold, overcrowded and desperately unhealthy. Disease was rampant. Enormous numbers of women died in labour.

Mosse vowed that he would change the city’s attitude to childbirth.

In the autumn of 1743, Mosse married again. His second wife was the sole heiress of the prosperous Archdeacon of Dublin who had died earlier that year. Mosse’s social status was always reasonable but the Whittingham marriage gave him the momentum he needed to commence his fund-raising campaign. And once he started, there was no stopping him.

Dublin may have been teeming with the poor and the homeless, but it was also a city of extreme wealth. Mosse was personally acquainted with many in the upper class. He listened to their obsessive talk about fashion and food, watched them stake their fortunes on the card tables, and joined them during the relentless social life of opera, plays, musical assemblies, concerts and masked balls.

And then he began to woo them.

His first patron was Dr Patrick Delany, the widely admired Chancellor of Christ Church Cathedral, who had recently lost a child at birth. With Delany’s help, Mosse slowly began to amass the shillings and pounds.

In 1744, Dublin’s Lord Mayor closed down ‘The New Booth’ theatre on George’s Lane after an excessively provocative performance. Mosse swiftly purchased the building and converted it into the 10-bed Hospital for Poor Lying-in Women, the first maternity hospital in the British Isles. By the end of its first year, 190 babies had been born with the loss of only one mother. Aided by two medical apprentices, Mosse supervised everything, funding the entire venture through the monies he managed to draw from Dublin’s rich.

The little Dublin hospital quickly became the talk of the British Isles and Mosse’s opinions were highly sought after. Now more energized than ever, Mosse began seeking funds to build a larger, purpose-built Maternity Training Hospital where other midwives and surgeons could train.

Fortunately, Mosse was a genius at fundraising. He was certainly the most successful fund-raiser of his day. Over the course of the 1740s, he organized an endless succession of theatrical shows, musical concerts and masquerade balls. The events proved a hit with Dublin’s elite and gave Mosse enough money to start building his new hospital. Of particular note were three performances of Handel’s Oratorios. He also raised over £11,000 from a series of lotteries that ran between 1746 and 1753.

In 1748, Dr Mosse leased a site of just over four acres on the north side of Great Britain Street (now Parnell Street). The area was described as ‘a piece of waste ground, with a pool in the hollow, and a few cabins on the slopes’. This is the site on which the Rotunda Hospital stands today.

Dr Mosse’s strategy for funding the Rotunda was both brilliant and bold. His first step was to commission a professional gardener to convert part of this wasteland into a Pleasure Garden, based on London’s Vauxhall Gardens. The new gardens included a Coffee Shop and a handsome Concert Hall where, in June 1749, Mosse staged the first of many concerts. Guests were given complimentary transport to the event on beautifully painted sedan chairs. Three months later, the gardens opened to the public. Admission was ‘one English shilling’. They quickly became a fashionable promenade and Mosse’s coffers were substantially buoyed.

Arguably Mosse’s greatest achievement was the Hospital Chapel, which remains one of the most powerful feats of creativity in Dublin to this day. Mosse knew that if he could convince Dublin’s wealthy Protestant citizens to worship in this Chapel, then a well-delivered tear-jerking sermon would compel his congregation to empty their purses onto the collection plate. But to lure the rich and famous, he would need a chapel that impressed. And so he commissioned Bartholomew Cramillion, one of the greatest stuccodors of his age, to design the altarpiece and the ceiling. The result was a mesmerising riot of saints, cherubs and angels, described as ‘the most extravagant figured plasterwork’ in the city. The coats of arms of the Hospital’s patrons, including those of Mosse, were painted upon the chapel walls. Sure enough, Dublin’s elite began to attend Sunday service here and, more relevantly, to pour their riches into Mosse’s hospital venture.

Then there was the Hospital itself. Based upon Leinster House, the building was designed, free of charge, by Mosse’s friend, the eminent architect Richard Cassels. Mosse himself designed the wards and delivery rooms. He favoured small rooms to the large open wards generally found in hospitals, as this enabled some form of control over the spread of infections such as puerperal sepsis. Mosse also planned the theatre, dining room, card-playing room and the circular Assembly Rooms from which the Rotunda takes its name. Completed after his death, the dances, banquets, recitals and card-nights that took place in these rooms continued to be the hospitals’ principal support well into the 20th century.

Despite all the money he raised, it was not enough. Even as the Lord Mayor laid the foundation stone for the £20,000 hospital in 1751, Mosse confessed to a friend that his personal fortune was barely £500.

Malicious rumours were also starting to circulate. It was whispered that Mosse was a fraud, that he had no intention of building his hospital but ‘meant to quit the Kingdom’ with his fortune and move to France or America. In 1754, Mosse was returning home from London when arrested at Holyhead. He was charged with having stolen £200 from the Hospital Lottery account. He managed to escape prison and lay low in a cabin in the Welsh mountains for three months. Many saw his flight as proof that he was an exposed swindler. In 1755, Mosse returned to Dublin and published a detailed statement of his finances, in which he successfully accounted for every shilling he had thus far raised.

Once exonerated, the Doctor recommenced his project. He successfully appealed to the Irish Parliament to help fund the Hospital, thereby raising its status from a charity to a national institution. In 1756, further good news arrived when the Hospital received its Royal Charter and the Duke of Bedford, the Viceroy of Ireland, became its first president. The New Lying-In Hospital’ was officially opened on 8 December 1757. Known today as ‘The Rotunda’, the 150-bed building was the first purpose-built maternity hospital in the world. Mosse was appointed its Master for the duration of his life. It was to prove a short tenure.

Less than a year later, Dr Mosse was taken seriously ill. He was quite simply worn out. Twenty years of intense concentration had taken its toll. Every day, he had been involved in raising money, organising events, meeting and charming the well-to-do, totting up figures and overseeing the construction of the whole complex. He had also helped to deliver several thousand babies. He was exhausted, heavily in debt and petrified about the prospect of arrest and imprisonment. Everything he owned was either sold or mortgaged. He had sacrificed everything to make the Hospital happen. He died on 16 February 1759 at the age of 47 and was buried in Donnybrook Cemetery. The whereabouts of his tomb puzzled Mosse’s biographers for many years but it was rediscovered in 1988. A memorial stone carved by his descendant Tania Mosse was unveiled to his memory on 20 September 1995, the 250th Anniversary year of the foundation of Mosse’s first Lying-In Hospital.

Mosse’s bust stands today in the front hall of the Hospital. He is also well recalled by plaques and road names in Portlaoise, the town of his birth. But the greatest memorial of his life is of course the Rotunda itself. Over 750,000 babies have been delivered in the Rotunda and a further 8,000 babies will be born here in 2009. The Rotunda is also at the forefront of global obstetrical services today and is universally recognised as a teaching hospital of the highest calibre. Dr Bartholomew Mosse can rest assured that his time was well-spent.