In Hidden Histories, we tell you the story of someone or something that you may not have heard of before, and today it's the turn of the wonderfully eccentric Honest Tom Steele, a Protestant Repealer who became Daniel O’Connell’s right hand man.

Listen to the podcast here:

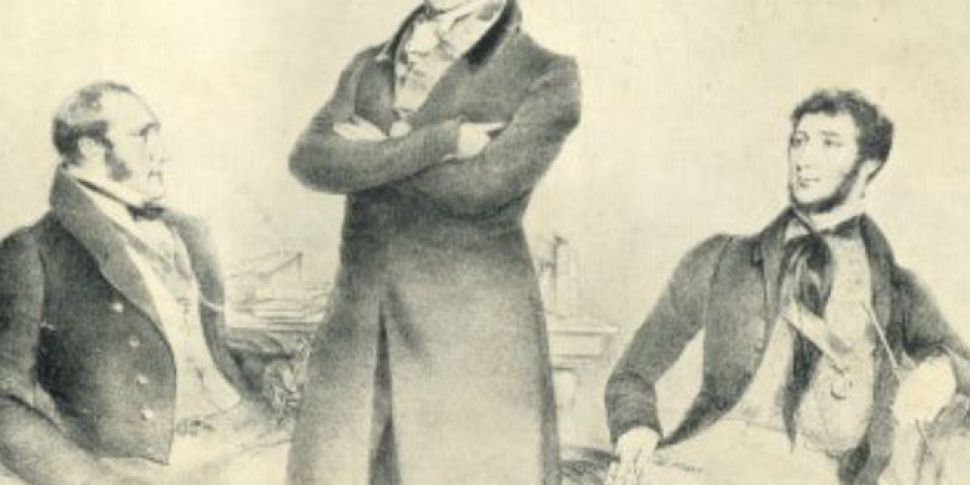

The annals of Irish history are littered with Protestants of English origin who effectively deserted the flag of their faith and ‘went native’. Few were more unusual than Honest Tom Steele, a graduate of Cambridge, a landed proprietor of Clare, an inventor of diving bells and a veteran of the Spanish Republican army who served as Daniel O'Connell's right-hand man for 24 years .

Tom Steele looked down at the turbulent waters of the Thames flowing beneath him and closed his eyes. His mind was a whirl of images – crumbling castles, bloody battles, beautiful women, broken promises, vast crowds and, omnipresent, his beloved Daniel O’Connell, the Emancipator of Catholics, alongside whom ‘Honest Tom’ had loyally served for 24 years. Tom opened his eyes, inhaled deeply and jumped.

Thomas Steele was an eccentric Protestant gentleman born in 1788 at his family home near Tulla in Co Clare. His forbears had served with distinction in Monmouth's Regiment during the reign of Charles II and received lands in Co. Tipperary by way of payment. In the early 18th century, a branch of the family relocated to East Clare where Tom’s grandfather secured ownership of considerable property. Tom’s father William perished when he was just a baby. The child was then raised by his bachelor uncle and namesake, Thomas Steele, at the sturdy new Georgian mansion of Cullane House outside the village of Quin. Young Tom received his elementary classical training from Rev. Dr. Fitzgerald at Ennis Grammar School. He was subsequently educated at Trinity College Dublin and Magdalene College Cambridge, graduating with an M.A. in 1820. His tutor considered him one of the best Greek scholars of his day.

Anyone at college during those years was inevitably swept up on the tide of romance, ignited by the Napoleonic Wars and given voice in the poetry of Keats and Lord Byron. When Tom’s uncle passed away in 1821, the 33-year-old inherited the substantial Cullane estate. However, rather than move into the barrack-like mansion of Cullane House, Tom set about restoring the ruins of Craggaunowen Castle, an ancient MacNamara tower-house on his land.

It was Tom’s dream that Cragganauowen would be the home where he and Miss Matilda Crowe of nearby Abbeyfield House, Ennis, would live happily ever after. For weeks on end, Tom sat gazing at Miss Crowe’s bedroom window from a large rock in the River Fergus, known today as Steele’s Rock. Tom was sure she would accept his advances. He was, after all, a much sought after young man, wealthy, intelligent, ‘tall with dark hair … and very good-looking’. Alas, Miss Crowe did not share his ‘ardent sentiment of attraction’ and turned him down.

Women should never underestimate what rejection can do to a man. One of Tom’s first moves was to write a bizarre letter to the elderly Pope Pius VII, urging him to convert to Protestantism without delay. More alarmingly, in 1823, he mortgaged the entire Cullane estate for £10,000, sailed for Spain and secured a commission in the ill-fated rebel army of Rafael del Riego. Tom duly served at the battle of Trocedero and the defence of Cadiz. He managed to avoid the death and execution which befell many of his fellow officers, returned to Ireland and wrote a dramatic personal account of the war.

With his political spirit now enflamed, Tom found a new cause awaiting him back home with the Catholic Association, founded by Daniel O’Connell in 1823. Catholic emancipation was the new goal. It fitted neatly with Tom’s vision of a new world order founded on freedom and happiness. Tom met O’Connell and offered to invest a large sum of money into the campaign. O’Connell duly embraced the Clare landowner to his cause and appointed him Vice-President of the Association.

Over the next decade, the friendship blossomed to such an extent that Tom erected a Catholic chapel at Cullane just so O’Connell could practice mass whenever he visited. (The altar was a cap-stone from a dolmen that reputedly stood at the dead-centre of Ireland, near Birr, until ‘Honest Tom’ recruited a team to shift it out west). O’Connell understood that the entire campaign could come to a shuddering halt if faction-fighting and secret societies within the Catholic organization became too intense. Tom’s absolute sincerity and utter disregard for money made him the ideal person to fill the post of ‘Head Pacificator’. Tom’s subsequent diplomacy within the ranks earned him the nickname ‘Honest Tom’.

In 1828, Tom had the honour of kick-starting O’Connell’s successful political career in Co Clare when he seconded O'Connell's nomination for the county against Vesey Fitzgerald. Having a Protestant landlord on his team certainly helped O’Connell crush Fitzgerald by 1,820 votes to 842 votes in what is generally considered to be the first major victory in the fight for Catholic Emancipation. Tom was by O’Connell’s side when the new Catholic Relief Bill was passed in February 1829.

During the 1830s and early 1840s, ‘Honest Tom’ continued to side with O’Connell, pumping much of his remaining fortunes into the mammoth campaign to repeal the Act of Union and restore Ireland’s constitutional independence.[2] He was a regular sight at O’Connell’s monster-meetings, frequently arriving dressed as an undertaker, carrying a coffin marked "Repeal on a hearse drawn by six black plumed horses. When not in undertakers’ garb, this imposing soul tended to kit himself in a shako and military frock. His trousers, often mud-splattered from driving horses, stopped just below his kneecaps. He disliked gloves intensely and never wore them. Contemporaries spoke of the ‘stern resolution stamped on his bronze face’.

He was not afraid to fight for his beliefs. In 1830, William Smith O'Brien, landlord of neighbouring Dromoland Castle, Co Clare, and Conservative MP for Limerick, mischievously assured Westminster that O’Connell did not have the support of any ‘gentleman’ in Co Clare. Tom recognized the slight and challenged O’Brien to a duel. They fought but no blood was spilled; ‘honour was satisfied’. In July 1848, six weeks after Tom’s death, Smith O’Brien found fame in Irish history when he led the Young Irelanders in their futile revolt against the police.

The success of the Repeal Movement began to dwindle after 1834 and Tom Steele’s fortunes went with it. In his spare time, he began to concentrate on horse-racing with the occasional stab at invention. As early as 1828, he had published a pamphlet offering remarkably sound solutions to making the River Shannon navigable. The pamphlet included drawings of an all-new diving bell, invented by Tom, which he had tested on the coast of Wexford. He seems to have used this bell with some success in later years. I know a man who claims Tom salvaged their dining table from the Royal George in 1840. The Royal George was the great flagship of the Seven Years War but sank in Portsmouth Sound on 29 August 1782 with a loss of 800 lives, including Admiral Kempenfelt.

Tom’s fiery passions could still be roused. In the summer of 1839 when the Dutch invaded Belgium, prompting Tom to offer his services to the King of the Belgians. The offer was turned down.

In 1843, a split began to emerge in the Repeal movement between O' Connell and those who felt a more aggressive stance was required. Tom took the side of his chief but was greatly upset by the collapse of the movement he had worked so hard to keep united. That summer, the British Government hardened their attitude to the Repealers and banned any further monster-meetings. Both O’Connell and Tom Steele were tried for sedition and sentenced to a year in prison.

By the time Daniel O'Connell died in Genoa on 15 May 1847, Ireland was already plunging into the nightmare of famine and fever. On a bright afternoon in April 1848, broken-hearted and penniless, 60-year-old Tom Steele made his way to Waterloo Bridge and threw himself into the Thames. His suicide attempt was thwarted by an alert passer-by and he was carried alive to Peele's Coffee House in Fleet Street where he was promptly charged with ‘attempting self-destruction’. He lay in agony for some months until ‘death came to the rescue’ on June 15, 1848. "Noble, honest, victimized Tom Steele!" exclaimed the London Standard, "fare thee well. A braver spirit in a gentler heart never left earth - let us humbly hope for that home where the weary find rest’.

The Cemeteries Committee had his remains removed to Dublin, and after some time placed them in a crypt in Glasnevin, close to the coffin of his chief. The Committee also paid for a fine monument.

This post was written by Historian Turtle Bunbury

"Visit Turtle Bunbury's website for more information or check his Wistorical Facebook page for his daily histories of an extraordinary cast of heroes, villains and eccentrics. Turtle's latest book, Vanishing Ireland (Volume IV) will launch in October 2013.