Newstalk Breakfast's resident historian Turtle Bunbury reveals a fascinating moment in time that you might not yet know about.

This Sunday will see Dublin and Mayo battle it out for possession of the Sam Maguire Cup, while next weekend, the Liam McCarthy will be destined for either Clare or Cork.

But who are the men behind these much coveted trophies? And what were their links to London and Michael Collins?

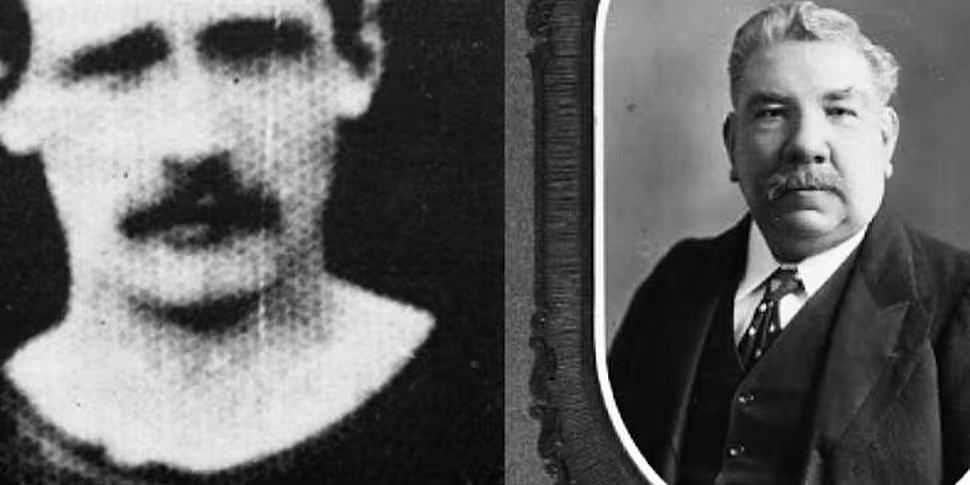

Amongst those gathered to watch the future Commander-in-Chief, then 19 years old, take his oath at Barnsbury Hall, Islington, was Liam McCarthy, the London-born councillor for Peckham, and Sam Maguire, a Protestant farmer's son from West Cork.

Indeed, it was Maguire who took the momentous step to introduce Collins to the IRB in the first place.

Over the next two decades, all three men were to dedicate their lives to the cause of Irish liberty. Their reward was not bountiful. Collins was gunned down at Beal na Blath, while both McCarthy and Maguire died prematurely and bankrupt.

Today, McCarthy and Maguire are household names on account of the All-Ireland cups for hurling and football which are named in their honour. But few know just how intricately both men were linked with the meteoric rise of Michael Collins.

London has long been a city to which Irishmen of every political and religious persuasion have been drawn. From the 1880s, the London branch of the IRB had played a vital role in keeping tabs on correspondence between the government in London and the British authorities in Ireland.

In the first decade of the 20th century, both McCarthy and Maguire joined the IRB in London. McCarthy was the older man by quarter of a century. Born in London in 1853, he was the firstborn child of Eoghan and Brigid MacCarthy, an Irish-speaking couple who had emigrated from famine-ravaged Ballygarvan, Co. Cork, two years earlier. The McCarthys formed part of an Irish community who settled on the South bank of the Thames near Lambeth.

Sport was an important aspect of daily life for the McCarthys. As a young man, Eoghan had been a notable athlete and wrestler, nicknamed 'McCarthy Capall' (McCarthy the Horse). By the age of fourteen, Liam and his hurly stuck were a regular sight on Clapham Common. His day job wielding a blacksmith's hammer on the railways ensured his arm muscles were in excellent shape. He was active in the London GAA from its foundation in 1886, having being a member of the Exiles of Erin Club. When the London County Board was formed following a meeting at Kensal Rise, North West London, on Whit Monday 1896, the 43-year-old was elected its first treasurer. He became President of the Board in 1898, holding the position until 1907 when succeeded by Sam Maguire. MacCarthy returned to the post in 1909 holding it until 1911.

In 1875, the 22 year old married Alice Padbury, the daughter of a 'Fancy Box' factory owner from Southwark. Liam joined the family firm but later fell out with his in-laws and set up a cardboard box making business of his own. Together with Alice and their eldest son William, they constructed the boxes on the kitchen table of their home in Peckham.

By the close of the 19th century, Liam was extremely active as a leader of London's ever expanding Irish community. The McCarthy home was a popular meeting place for Irish emigrants arriving in the British capital in pursuit of a job and a place to stay. In 1900 he was elected as an independent Councilor to the Borough of Camberwell for North Peckham and he was subsequently elected to many sub-committees including those dealing with Public Health, Libraries and Sick Benefit. He kept his Council seat for 12 years.

McCarthy did an enormous amount to promote Irish sport and social gatherings across the city. As well as his work with the IRB, he was Vice-President of the Gaelic League, a member of the London Irish Volunteers and chairman of the London (GAA) County Board. He was a major patron of the sport and spent much of his own money in London sponsoring cups and medals for club games, as well as paying for hurling sticks. He also financed projects that promoted the Irish language and educated the Irish in London in the history and mythology of their native land.

The Secretary of the London GAA at this time was a young post office worker from Clonakilty, West Cork, called Michael Collins. He had arrived in London in 1905, aged fifteen, and found work in the same Post Office where Sam Maguire was working.

Born in 1879, Maguire grew up on the 200 acre family farm at Mallabraca near the town of Dunmanway in West Cork. Although they were Church of Ireland, the Maguires had successfully integrated with the Catholic community and were held in high esteem. Sam was the youngest of four brothers, with two sisters who never married. He was educated at the Model School in Dunmanway and at the National School in Ardfield, where Collins subsequently attended.

The tall, slim, broad-shouldered 20-year-old arrived in London on the eve of Queen Victoria's death and went to work in the Post Office headquarters at Mount Pleasant near King's Cross.

Although he had never played football in Ireland, he joined London Hibernians. In those days, there was both a 'home final' and an 'All-Ireland Final' in which the All-Ireland and All-Britain champions were paired against one another. Maguire captained London Hibernians in the 1900, 1901 and 1903 finals. The team lost on all three occasions.

In June 1906 he again captained the side in the final of the Croke Cup, the last time he played in Jones's Road (later Croke Park). The following year, he joined the administrative department of the London GAA, becoming Chairman of the London County Board and a regular delegate to the Annual Congress of the GAA. He later became a trustee of Croke Park. The Vice-Chairman of the London County Board at this time was Liam McCarthy.

Maguire had become an influential member of the London IRB by the time he befriended Collins at the Post Office. 'You bloody South of Ireland Protestant' was how Collins often referred to him but the two West Corkmen became close friends. In November 1909, Maguire swore Collins into the IRB.

By the time the Easter Rising in Dublin, Maguire was head centre of the London IRB. McCarthy was also highly ranked and it was he who persuaded Collins to return to Dublin and take his place alongside Pearse in the GPO. McCarthy was a passionate supporter and patron of Pearse's St Enda's school; he sent his son Eugene there for a year.

Maguire was urged to remain at his job in London as he would be much more valuable as an informer within his civil service. Most communication at this time went through the post office and Maguire was often able to intercept Official State Documents which provided vital insights into just what 10 Downing Street was planning to do in Ireland. Many of the Irishmen working in London's post office at this time were sworn members of the IRB.

In the summer of 1919, Collins was elected President of the IRB. Maguire became an integral part of his intelligence network, playing a key role in raising funds and smuggling arms into Ireland during the War of Independence. He frequently travelled across the Irish Sea to Dublin on the night mail with information that he dare not write down. He paid the fare from his own pocket and refused to accept any money offered for expenses.

Maguire's cover was vital and the wily Protestant bachelor played the game well. On one occasion, he?alerted? His London employers at the Post Office to a stack of rifles which belonged to the company brigade, warning that they were likely to be stolen by those 'unscrupulous Sinn Feiners'. His superiors did nothing and two nights later the rifles had mysteriously vanished, destination Ireland.

Meanwhile, Collins and McCarthy's friendship was also blossoming. Acting as de facto Minister for Finance, Collins had established a 'National Loan', primarily to raise funds for the operation of the Irish Volunteers who around this time became known as the Irish Republican Army. McCarthy was appointed London treasurer for the Loan which, by the end of August, had amassed £250,000 [c. €12 million in 2010].

McCarthy purchased £50 [c. €2,700 in 2010] of certificates on behalf of himself and his two sons, William and Eugene. When the loan was redeemed, he used the money to purchase a silver cup which, like the Sigerson Cup of 1911, was modelled on an ancient Gaelic Meither, or loving cup. He offered it to the Central Council of the GAA as a perpetual trophy for the All-Ireland hurling champions. And so the Liam MacCarthy Cup was born.

During the Civil War, all of the GAA clubs in London adopted an Anti-Treaty stance but McCarthy stayed loyal to Collins.

When McCarthy died after a long illness on 28th September 1928 and was buried in an unmarked pauper's grave in Dulwich Cemetery, London. On Easter Sunday 1996, 68 years after his death, the Dulwich Harps GAA club erected a headstone over his grave.

[In 1992 the original Liam McCarthy Cup was retired. As chance would have it, Tipperary were the last team to claim the original while Kilkenny were the first team to win the 'new' McCarthy Cup, an exact replica was produced in 1992.]

Sam Maguire continued to play a key role during the War of Independence, perhaps most notably when he saved one of Collins's death squads from certain capture as they were about to assassinate a British officer in London.[vi] Together with his second-in-command, Reggie Dunne, he also devised a plan to kidnap 25 Westminster MPs who were to be held in retaliation for hostages taken in Ireland.

The plan was seriously considered but abandoned when the British government sued for peace. Collins duly arrived back in London to negotiate the Anglo-Irish Treaty with Lloyd-George, Churchill and the British cabinet.

In November 1921, while the Treaty negotiations were underway, Cathal Brugha, Minister for Defence, sent two IRB men to London to collect some arms. In a sign of things to come, they were told to keep the deal a secret from both Collins and Maguire.

The following June, Maguire became embroiled in one of the most controversial episodes of the Troubles with the assassination of the staunchly Unionist Sir Henry Wilson, a friend of Churchill and the Northern Ireland Government's adviser on security.

Sir Henry was shot dead outside his home in Belgravia on 22nd June 1922. His assassins were Reggie Dunne, Maguire's deputy, and one-legged Joe O'Sullivan. Both men were captured, convicted of murder and hanged six weeks later.

The historian Tim Pat Coogan described Sir Henry's assassination as 'one of the most indefensible, inefficient and hopelessly heroic deeds of its kind'.

Precisely how involved Maguire was remains unclear. Dunne and O'Sullivan may have been acting of their own accord. They may have been following an order given by Collins some time previously. In 1953, Joe Dolan, one of Collins's former intelligence staff, stated that Collins had given this order to Maguire who he in turn passed it on to Dunne and O'Sullivan. Coogan also believes the order was given directly by Collins and delivered via Peg ni Braonain, a young Cumann naBan member.

However, Collins denied giving the order. His supporters generally agree that he gave the order but, amid the excitement of the Treaty and ensuing debates, he either forgot or failed to cancel it. His detractors hold that Collins simply lied to save his skin, disowning Dunne and O'Sullivan in the process.

Britain demanded vengeance for Sir Henry's death. Dunne and O'Sullivan appear to have been acting in support of the anti-Treaty forces who, headed up by Rory O'Connor, had been occupying the Four Courts since mid-April. Six days after Sir Henry's assassination, under pressure from London, Collins ordered the Free State Army to bomb the Four Courts, thus igniting the Civil War.

Both Maguire and McCarthy were horrified by the ensuing Civil War.

There are two versions of Maguire's post-war story. One has him flee London in the wake of Sir Henry's assassination, with Scotland Yard hot on his case. When the truth of his involvement in the IRB became known, he was stripped of his £4,000 pension from the Post Office, a devastating financial blow at that time. He took the pro-Treaty side during the Civil War and secured a post within the Free State's new Civil Service. However, his attempts to modernize and Irish-ify the British system brought him into conflict with his superiors and he was dismissed with a paltry £100 [c. €6,000 in 2010] pay off and no pension.

The second story says that he remained in England until 1923 when he returned to Dublin and took a job in JJ Walsh's Department within the Posts and Telegraphs. His £4,000 [€250,000 in 2010] pension was moved from London to the Irish Civil Service. However, on 29th December 1924 he was summarily dismissed from his post as it was suspected that 'the person concerned has been in close and active association with a conspiracy, the object of which was to suborn from their allegiance members of the Army and other State Services, with a view to renewing the attempt to subject the Government to pressure of an unconstitutional nature'. As the GAA Museum says, 'Maguire was dismissed without pay; efforts by him for an investigation into his alleged role were unsuccessful and he never got the chance to prove his innocence.'

Penniless and in rapidly declining health, he returned to the family farm at Mallabraca, Co. Cork in 1926. He died of tuberculosis on 6th February 1927. He was 47 years old. On his final visit to Dunmanway he reputedly gave away his last £5 [c. €330 in 2010], saying he would not need it anymore. He was buried in the Protestant cemetery with a grave marked by a Celtic cross. Shortly after his death, some of his friends in Dublin organized a collection, using the money to purchase a cup which was modelled on the Ardagh Chalice and made by Hopkins and Hopkins of O'Connell Bridge. The cup was presented to the GAA in honur of a man who remains the only Protestant to have captained a team in the Senior Football Final. Kildare was the first county to win the cup in 1928.