Listen to Turtle detail the San Patricos here:

<iframe frameBorder='0' height='80' style='width: 100% !important; height: 80px !important;' src='http://www.newstalk.ie/embedded_media_iframe.php?audioURL=http://cdn.radiocms.net/media/001/audio/000004/35018_media_player_audio_file.mp3&audioDesc=Hidden Histories with Turtle Bunberry: John Reilly'></iframe>

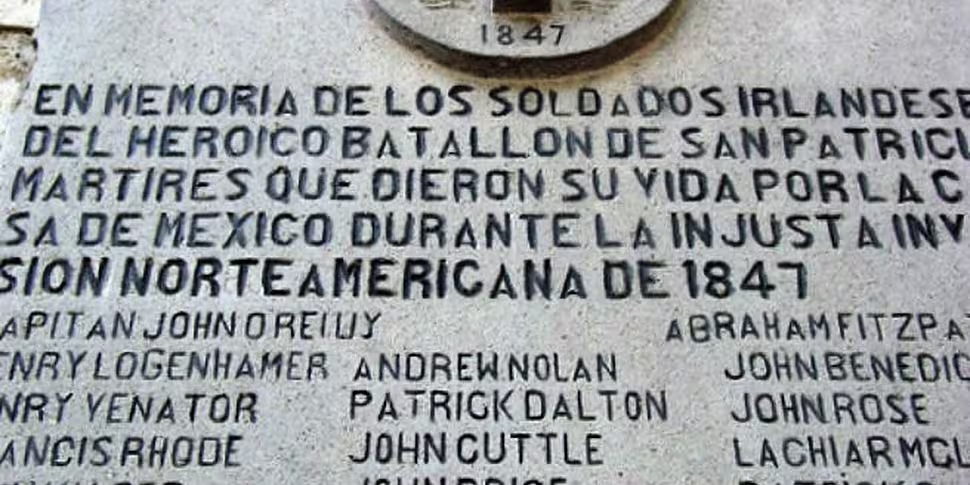

In the winter of 2001, I chanced to stay with friends of friends in the affluent suburb of San Ángel outside Mexico City. It was my first time in Mexico and, at my hosts suggestion, I went for a walk around the neighbourhood. My attention was drawn to a marble monument, emblazoned with a Celtic cross, fixed to a wall at one end of a cobblestone plaza in San Angel. My Spanish is lousy but even I could see that this was a memorial to Irishmen. ‘Los Soldados Irlandesa’ were the ‘Heroico Battalon de San Patricio’, who fought for Mexico during ‘la injusta invasion Norte Americana de 1847’. Their commander was Captain John Riley and amongst the 71 names that leapt out were those of Santiago O’Leary, Kerr Delaney, William Wallace, Francis O’Conner and Lemuel Wheaton. Lisnavagh, the house where I grew up in Ireland, was built in 1847. This rather wonderful Mexican-Irish discovery prompted me to wonder anew at what else was going on upon Planet Earth back in 1847. But first to Mexico …

Towards the end of August 1850, Don Ignacio Jose Jimenez, curate of the parish church of the Assumption of Our Lady in Veracruz on the east coast of Mexico, closed his eyes and prayed aloud as the body of John Riley was lowered into the ground. Whether Jimenez knew the deceased is unknown but that evening he observed in the parish register that ‘Juan Reley’ was ‘forty five years of age, a native of Ireland, unmarried, parents unknown’. He also noted that the dead man had died ‘as a result of drunkenness’ and ‘without sacraments’. It was certainly an inglorious end for the soldier from Connemara who had commanded the infamous Saint Patrick's Battalion just three years earlier.

Once described as the ‘most hated man in America’, John Riley [sic] was born in Co. Galway in about 1818. As the son of a tenant farmer from barren soils of Connemara, he belonged to a people who one contemporary described as ‘a rare breed … wild like the mountains they inhabit’. Very little is known of his early life save that his family moved to the bustling new town of Clifden in the early 1820s, perhaps driven by the so-called ‘Forgotten Famine’ which ravaged Connaught for seven long years at this time.

Riley was a teenager when Daniel O’Connell secured emancipation for Irish Catholics. But prospects for his religion and generation remained decidedly thin and, perhaps following the lead of an uncle, he joined the British Army. Nothing is known of this part of his life but he subsequently sailed to Canada, from where he made his way to Michigan and found work as a dockside labourer. It is believed he left a wife and son behind him in an Ireland about to face into the horrors of the Great Famine.

In September 1845, Riley enlisted in the US Army. Seventy years after it won its independence, the USA was about to launch its first foreign invasion with an amphibious assault on Mexico. Like every war, the Mexican War was territorial. It had begun a decade earlier when Texas effectively established its independence from Mexico in 1836, the year Davy Crocket and his allies died at the Alamo. In 1845, the Republic of Texas voluntarily became part of the USA. Incoming US President James Knox Polk – whose forbears came from Lifford, Co. Donegal - seized the opportunity to lay claim to all the land as far south as the Rio Grande. Mexico understandably saw this as an incursion, maintaining that Texas’s border were much further north at the Nueces River. Polk put the US onto a war footing and persuaded Congress to authorize 50,000 troops and $10 million to support the war. Amongst the thousands of newly arrived Irish immigrants who piled into the recruiting centres at this time was John Riley.

Two days after he enlisted, Riley was sent south to Texas with the 5th Infantry Regiment (also known as the "Bobcats"). K-Company, to which he had been assigned, was one of five companies dispatched by Polk under the command of future US President General Zachary Taylor to protect the disputed zone.

Riley evidently detested his time in the US army. This was an age when there was a xenophobic hatred of Catholics in the WASP-controlled US, particularly amongst the West Point educated officers in the army who invariably treated European immigrant conscripts like dirt. It didn’t help that Catholic soldiers were prohibited from celebrating Sunday Mass.

In April 1846, Riley deserted the US Army and somehow linked up with the Mexicans. General Pedro de Ampudia, the Cuban-born commander-in-chief of the Mexican army, quickly recognised Riley’s leadership skills, appointed him 1st Lieutenant and gave him command of ‘a company of 48 Irishmen’ in the Mexican Army. For the most part, these men came from Dublin, Cork, Galway and Mayo. The Mexicans referred to them as ‘Los Colorados’, after their red hair and ruddy, sun burnt complexions. A month after they were established, Riley’s company manned the canons during an unsuccessful six-day siege of the American garrison at Fort Texas along the banks of the Rio Grande.[i]

During the summer of 1846, the Irishmen combined forces with the Legión de Extranjeros (Legion of Foreigners), a ragtag mixture of mostly Catholic Germans, French, Italians, Poles, Scots, English, Spaniards, Swiss and Mexicans. There were also a number of second and third generation Canadians and Americans, and several African-American slaves who had escaped from the American South. By September, these men had been formed into one unit, the Batallón de San Patricio, St. Patrick’s Battalion.

There are many reasons why such men joined the San Patricios. Aside from their own unhappy status in the US army, the Catholic soldiers were undoubtedly appalled by the manner in which General Taylor’s unruly troops rode roughshod over the Mexican Catholics, ravaging their women and plundering their churches.

For others, it was about the money. American soldiers were paid $10 a month pay, with three months advance pay, and the promise of 160 acres of farmland. The Mexican army offered better wages than the US army and a real chance at promotion, as well as land grantsstarting at 320 acres. The temptation for a once landless Irish labourer to secure that much land must have been hard to resist, particularly as they passed through village after village of beautiful Mexican women.

At any rate, on 21 September 1846, an estimated 175 men gathered beneath the green flag of the San Patricios in northeast Mexico, in an old fortress at the foothills of the Sierra Madre Oriental. The ensuing Battle of Monterrey was something of a last stand for Ampudia’s Mexican Army of the North who had been retreating from the US for several long and disheartening weeks. The San Patricios were a vital cog in this Mexican force and, during the four day-long battle, Riley’s men showed their mettle, blocking several separate assaults on the fortress and killing a large number of US soldiers. However, the Americans howitzers gradually reduced Monterrey to rubble and Taylor’s infantry streamed in to engage the Mexicans in hand-to-hand combat. At the end of the battle, over 500 men lay dead.[ii] Ampudia negotiated a two-month armistice which enabled the Mexican army to disperse with full arms and six of their 31 guns, while the US retained the fortress. President Polk was livid with Taylor, arguing that he had no authority to negotiate truces, only to "kill the enemy" as ordered.

But the legend of the San Patricios had been born. Huge numbers now flocked to the battalion with some estimating its numbers to be over 700 men. In due course, they re-assembled at San Luis Potosí in central Mexico where a group of nuns embroidered their distinct Green silk flag. George Kendall, an American journalist in Mexico at the time, described the flag as having a harp on one side, surmounted by the Mexican coat of arms, with a scroll that read, ‘Libertad por la Republica Mexicana’ (‘Liberty for the Mexican Republic’). Under the harp was the Irish motto, ‘Erin go Bragh!’ (‘Ireland Forever!)

From San Luis Potosi, the San Patricios marched north to Coahuila to join the army of General Santa Anna, the infamous ‘Butcher of the Alamo’. They were soon in action at the Battle of Buena Vista, which began when the Mexicans intercepted a letter revealing that half of Taylor’s army had been deployed elsewhere. Santa Anna consequently launched a full-blown attack, gambling heavily on a win. He personally led the army of 20,000 Mexicans into the field on 23 February 1847. [iii]

Riley’s men were placed in command of the Mexican’s three heaviest canons (18 and 24 pounders) which they quickly positioned on high ground over the battlefield, providing vital covering fire as the Mexican infantry advanced. A small division under future Mexican PresidentManuel Lombardini slipped away on foot to surprise attack one of the US artillery batteries, bayoneting the luckless Americans and adding their six pound canons to the Mexican arsenal.[iv] Taylor was so infuriated by this brazen attack that he ordered a squadron of dragoons to ‘take that damned battery’. They were unable to do so and those who returned alive came back wounded and blood-soaked.

However, the battle did not go Mexico’s way. The San Patricios were obliged to provide more and more covering fire to retreating infantry as the afternoon wore on. They then embarked upon an ill advised shoot out with the more powerful American artillery which resulted in almost a third of the battalion being killed or wounded. In total, 1,800 Mexicans and 672 Americans died in what was ultimately a catastrophic defeat for the Mexicans. A number of Irishmen were subsequently awarded the War Cross by the Mexican government for their conduct, and many received field promotions.[v]

Although they excelled as artillerymen, the San Patricios were now ordered to re-form as an infantry battalion by personal order of Santa Anna. Overall command of the Foreign Legion of Patricios was given to Colonel Francisco R. Moreno, while Riley was placed in charge of the first company and Santiago O'Leary headed up the second.

As infantrymen, it was far more likely that the San Patricios would be captured. And as deserters from the US Army, capture meant execution. Thus, during subsequent battles, when their fellow Mexican troops began to waver and seek surrender, the San Patricios threatened to shoot them unless they put their lily-white hands right back down again. This was particularly the case at the Battle of Cerro Gordo, but it was to no avail as, when the Irishmen were otherwise occupied, the Mexicans broke and ran, leaving the San Patricios to fight the U.S. troops in hand to hand combat.

On 20 August 1847, two days after the defeat at Cerro Gordo, Santa Anna gave a verbal order that the San Patricios were to ‘preserve the point at all risk’. The ‘point’ was the Convent of Churubusco and it was just outside the walls of this abode that the San Patricio veterans set up a battery of five heavy canons and tried to hold off the American advance, supported by two battalions of raw and untested young Mexican militiamen. Disaster ensued when a stray spark from one of the San Patricio canons scorched into a wagon that had just arrived with badly needed back-up ammunition.[vi] A huge explosion ripped through the air and among those badly injured by fire were Captain O'Leary and General Anaya. As the Americans began to outflank the defenders, the San Patricios and their Mexican allies reluctantly retreated into the convent.

With an inevitability that is common to gunslinger westerns, the San Patricios now awaited certain death. Ammunition was running low so they made every shot count, aiming directly at the American officers, particularly those whom they had known from their past life when they too had been in the US army. When a Mexican officer attempted to hoist the surrender flag, a Mayo-born officer called Patrick Dalton ripped it down. When other Mexicans attempted to do the same, they were shot and killed by the San Patricios. The fighting was now brutal hand-to-hand combat, sabres, bayonets, blades, fists. Eventually, the US overwhelmed them, ‘ventilating their vocabulary of Saxon expletives, not very "courteously," on Riley and his beautiful disciples of St. Patrick’. [vii]

It is believed that 35 San Patricios died at Churubusco and 85 were taken prisoner, including General Anaya, John Riley, Santiago O’Leary and Patrick Dalton. A further 85 managed to escape with the retreating Mexican army and were stationed at Querétaro during the Battle of Mexico City two weeks later.

71 of the 85 captured San Patricios were charged with desertion in a time of war, including 48 Irish and 13 Germans. They were court martialed and sentenced to death by an American army baying for blood. These men had no legal representation. Twenty-four men, including Riley, were spared the death penalty because they had deserted before the official declaration of war on Mexico. Instead they received ‘fifty lashes on their bare backs’, were branded with the letter 'D' for deserter, and forced to wear iron yokes around their necks for the remainder of the war. Some were branded on the hip, while others were branded on the cheek. Riley was branded with red-hot irons on both cheeks for good measure.

Some claimed they had been drunk when they joined. Others said they had been effectively press-ganged. Those men were given the unhelpful reassurance that they would be shot by firing squad rather than hung by a rope like everyone else. For most, it mattered not why they joined. You were still a dead man.

Over 9,000 US soldiers deserted during the Mexican-American War, but the San Patricios were the only ones who were punished by hanging. Fifty men were hung between 10th and 13th September between the well-to-do suburb of San Ángel, the village of Mixcoac and the hill of Chapultepec from which the Aztecs once ruled. According to one American witness, Dalton, who had been vocal about the mistreatment of prisoners, was ‘literally choked to death’. Larry O’Loughlin, the playwright whose one-man show ‘100 More Like These’, starring Stephen Jones, is based on the events of 1847 recalled meeting an old man in San Ángel in 2008 who maintained that the spirits of the dead Irelandesa still circulated through the streets.

In one of the most spectacular moments of the entire war, Colonel William Harney ordered the mass execution of 30 prisoners at one moment during the battle of Chapultepec. Harney choreographed the hangings to tale place at the precise moment that the US flag replaced the Mexican one on top of the town’s citadel, in full view of both armies. A witness recalled how ‘ands tied, feet tied, their voices still free’, the condemned men managed to let out a final ‘Braveheart’ like cheer for the Mexican flag before the nooses tightened. Amongst these men was Francis O'Connor who had lost both his legs the previous day. When the army surgeon explained O’Connor’s condition, Harney replied with cool villainy, ‘Bring the damned son of a bitch out! My order was to hang 30 and by God I'll do it!’ The Mexican government described the hangings as ‘a cruel death or horrible torments, improper in a civilized age, and [ironic] for a people who aspire to the title of illustrious and humane’.

Riley and the other men remained prisoners until the close of the war. On 2nd February 1848, the US and Mexico signed the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which gave the US undisputed control of Texas, established the US-Mexican border along the Rio Grande River, and ceded to the United States the present-day states of California, Nevada, Utah, and parts of Colorado, Arizona, New Mexico, and Wyoming. In return, Mexico received US $18,250,000 (c. $447,967,308 today)—less than half the amount Polk had offered for the land before the war.

In June 1848, the San Patricios were revamped into a battalion of two companies, with the newly promoted Colonel Juan Riley in command. However, they were immediately plunged into the whirlpool of Mexican politics when one of Riley’s captains, a Scotsman calledJames H Humphrey, was implicated in an abortive military coup. Riley also came under suspicion, the battalion was disbanded and its officers exiled. The official line was that it was disbanded due to budget cuts.

Colonel Riley was ‘retired’ and sent to Veracruz, with full pay, presumably on the basis that he would sail back to Europe. He now ‘slipped back from the lips of fame’. In contact with his wife and son in Ireland, he sought to borrow money to send to them so that they might survive the ravages of the Famine. Don Juan Reley [sic] may even have intended on returning to Ireland to join them. Tragically, he appears to have contracted yellow fever at about this time and, turning to the bottle, succumbed and died. (This was not the finale that Hollywood wanted for its epic movie ‘One Man Hero’ in which Tom Berenger’s Riley dies before a firing squad).

Most of the surviving San Patricios did leave Mexico at this time, although a few undoubtedly stayed. James Fennell and I encountered a freckle-faced, red-headed Spanish-speaking young man in Cuernavaca in 2001 who looked at us in great surprise when we suggested he might be of Irish origin.

The Battalion continues to be revered in Mexico to this day, particularly on 12 September (the accepted anniversary of the executions) and St Patrick’s Day. Many schools, churches and streets in Mexico are named for them. In 1997, Ireland and Mexico jointly issued commemorative postage stamps to mark the 150th anniversary. In 2004, the Mexican government also presented a commemorative statue to the Irish government in ‘perpetual thanks for the bravery, honour and sacrifice’ of the San Patricios. This now stands in Clifden, birthplace of John Riley, a town which flies the Mexican flag every September 12th. The Chieftains and Liam Neeson are set to collaborate on a song to commemorate the San Patricios in 2010.

This post was written by Historian Turtle Bunbury

"Visit Turtle Bunbury's website for more information or check his Wistorical Facebook page for his daily histories of an extraordinary cast of heroes, villains and eccentrics. Turtle's latest book, Vanishing Ireland (Volume IV) will launch in October 2013.