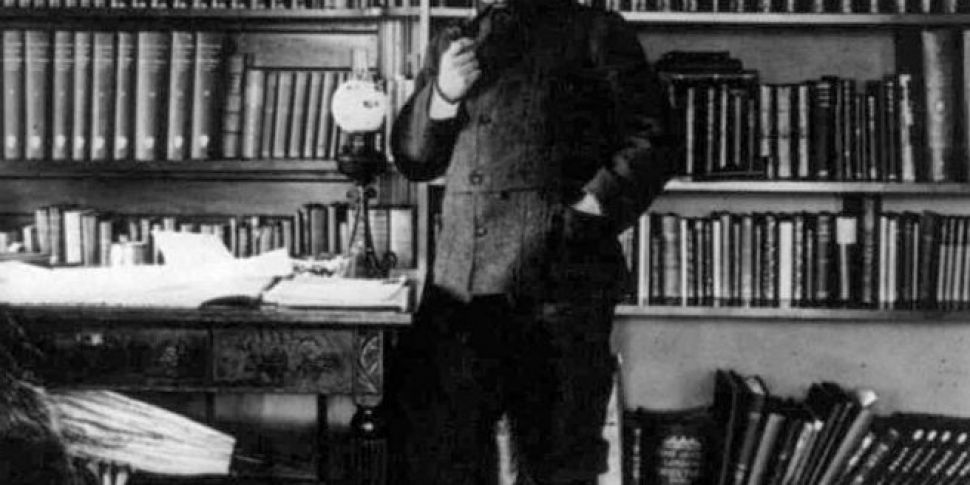

Few authors are as famous and divisive as Rudyard Kipling. Beloved for his lyrical poetry and vivid stories he brought foreign lands to life for his audiences back home. His tales continue to fascinate children and adults alike to this day. For all his popularity and skill though Kipling remains a divisive figure and George Orwell famously dubbed him a “prophet of British Imperialism”.

Kipling’s story is far from simple though. Born in Bombay, where his father was Principle of an art school, his was a thoroughly Anglo-India upbringing. Home was the smells, breath, and hazy landscape of India while his nursery rhymes and childhood stories were all told in the local vernacular by his Indian nanny.

So immersed was he in the local culture and language that English became Kipling’s second language. He noted himself how he would speak with his parents in English “haltingly translated out of the vernacular idiom that one thought and dreamed in”. Like many sons of Britain’s empire Kipling had an identity wholly different from that of the home islands.

At five years old though Kipling was ripped from the warm bosom of India and dropped in a boarding house in Portsmouth. They would spend six miserable years here under the care of Mrs Sarah and Captain Pryse Agar Holloway. While such boarding was commonplace for children of those serving abroad, the Holloway’s level of cruelty and neglect was not.

What is surprising is that the Kipling’s had welcoming relatives in London who they spent wonderful Christmases with. Why Kipling and his sister Alice were sent to live with uncaring strangers over loving relatives is unclear but it seems as though his parents were unaware of Kipling’s poor treatment.

In 1877 his mother returned from India and Kipling and Alice were saved from the terrible house by the sea. Though a traumatic experience the time spent with the Holloways, as Kipling noted himself, may have helped foster his literary instincts and imagination. The worlds created in Kim and The Jungle Book are near paradises that can almost be touched and where a mind could disappear.

Kipling’s return to India came once he finished with school. Too poor to afford tuition and not smart enough to earn a scholarship Kipling was forced to look for work. His father soon secured him a position as assistant editor at a local paper in Lahore and Kipling, just shy of 17 years old, began to make his way back toward India.

This return proved to be an enlightened awakening as Kipling rediscovered his home and identity. For the next seven years Kipling worked as a journalist across modern India and Pakistan. Consumed with a passion for the written word Kipling spent his spare time composing poems and stories.

These proved quite popular and Kipling soon became noted as much for his creative tales as for his journalism and work rate.

In 1889 Kipling left India for life in London. Here his stories proved massively popular in all the right circles and Kipling’s star began to rise. There would be no relenting in the growth of his popularity either. What is most surprising though is that, after this move, Kipling would never again live permanently in India.

The subcontinent would never leave Kipling’s heart though.

In a life of travel and adventure India always seemed to re-emerge. While living in America he remembered the jungles of his home and began composing the story of Mowgli, Baloo, and Bagheera that proves so popular still.

But what exactly was his relationship with India? Was he a native born son or another imperial advocate? Are the two mutually exclusive? And what can we learn from his writings?

Talking Books’ host Susan Cahill talks with Professor Daniel Karlin about the life and identity of Rudyard Kipling and the new edited collection of his Stories and Poems.

Susan also talks with Congo born writer, poet, academic, and journalist Alain Mabanckou about his own experiences and why it’s so important that African authors write about the real lives and stories of the great continent.

This week’s music to read to

The first part of the show opens and closes with Bád Bán by Colm Mac Con Iomaire with the show itself ending on Sylvain Chaveau’s La Brasiere de Tristesse.