Few Native American figures are as immediately recognisable as Sitting Bull. Born into the Hunkpapa branch of the Lakota tribe by the Grand River in modern day South Dakota, circa 1831, he rose to prominence as a brave warrior, defiant chief, and respected holy man. His role in orchestrating the defeat of the 7th Cavalry at the Battle of the Little Big Horn ensured Sitting Bull would be remembered by history. Yet there was far more to this great man than being the victor at Custer’s Last Stand.

At first named Jumping Badger. At ten, however, he began to show the talent and bravery that would distinguish him in later life when he killed his first buffalo. Four years after this milestone Jumping Badger took part in his first raid against a group of Crow warriors. He again displayed immense bravery by counting coup on the Crow, riding forward and striking or touching an enemy warrior with a harmless stick.

Jumping Badger’s father was so impressed with the youth’s actions during the raid that he gave the boy his own name of Sitting Bull. Describing a stubborn buffalo that plants itself on its haunches to fight instead of fleeing this was a name for a brave and immovable warrior. This renaming was a great honour and formed part of the boy’s transition into manhood. He was also presented with his first warhorse, hide shield, and eagle’s feather—the token of a great deed done. Yet this was only the start of Sitting Bull’s legacy and he would die with many more feathers in his cap.

As a young man Sitting Bull continued to prove himself a fearless warrior and hunter and brought much meat to the lodges lot of the Hunkpapa. He also studied the rituals and mysteries of the Lakota, becoming a holy man who came to be regarded as having ‘strong medicine’. While this was going on, however, the United States was expanding its territory and settlements to the detriment of the Native tribes. In 1862 growing animosity between the eastern Dakota and white settlers erupted into the Little Crow War.

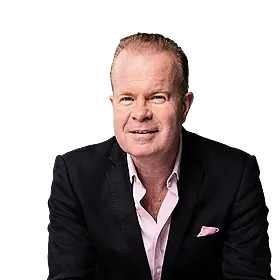

Early cabinet card of Sitting Bull by Orlando Scott Goff, 1881

Early cabinet card of Sitting Bull by Orlando Scott Goff, 1881

Provoked by hardship, broken treaties, and exploitation and impoverishment by Indian agents, the Santee tried to drive the whites from the Minnesota River valley. Though embroiled in the Civil War the Federal government dispatched army units to quell the violence. After surrendering 38 leading Santee were hanged, the Minnesota reservations abolished, and the tribes expelled from the state. Survivors fled west in search of game or security, interacting with other tribes as they travelled.

It was through these displaced Santee that Sitting Bull got his first inkling of what the ‘white man’ was like. These negative reports were soon confirmed as military expeditions pushed into Dakota and Lakota territory; exacting revenge for the aggression of ’62 and trying to pulling the teeth of the remaining Sioux, the collective name for Lakota and Dakota. Part of this campaign saw Sitting Bull, with fellow chiefs Gall and Inkpaduta, defend a village against the forces of General Alfred Sully.

Though few of the encamped tribes had been involved in violence against the US, Sully ordered his troops to advance and used his artillery to shell the camp. The Sioux, armed with bows and a few rudimentary guns, stood little chance against the army’s rifles and cannons and were forced into a fighting retreat. This targeting of ‘civilian’ camps had long been a feature of war between tribes on the plains. The US Army’s adoption of this tactic proved disastrous for the Plains Indians, however, thanks to the technological gap.

After this first interaction with the ‘white man’ Sitting Bull became belligerent toward the US Government. He joined Red Cloud’s War, leading attacks on US positions in 1866. When the Treaty of Fort Laramie was signed in 1868 Sitting Bull wanted no part of the peace. He mistrusted the promises made and continued to raid the upper Missouri area into the 1870s. This aggressive behaviour kept the US expansion across the northern plains in check, for a short time at least.

'The Custer Fight' by Charles Marion Russell, 1903

'The Custer Fight' by Charles Marion Russell, 1903

This was all to change when George Armstrong Custer led a military expedition into the Black Hills in 1874. A sacred region for many Native American tribes the Black Hills had been part of the lands set aside for the Lakota, Dakota, and Arapaho in the Treaty of Fort Laramie. Reports of gold warranted investigating though and so Custer, an American hero adored as much for his flamboyant character as his fearless actions during the Civil War, was dispatched. His mission proved there was gold and thousands of adventurers invaded on the Black Hills.

Tensions mounted as the tribes used violence and terror to secure their treaty-mandated land from the encroaching miners and settlers. There was little that could withstand the greed for gold, however, and in November 1875 the Federal government ordered all Sioux back to their reservations. Those who refused were declared hostile the following February and three army columns were dispatched to subdue them. Sitting Bull’s defiance since the Treaty of Fort Laramie attracted the rebellious and resistant. Those who opposed the US invasion now flocked to his camp.

Sitting Bull actively sought out those who would wish to join his camp and fostered a feeling of unity through the sharing of supplies and provisions with any needy arrivals. These policies saw Sitting Bull’s extended camp grow to an estimated 10,000 strong. It was onto this hive that Custer’s 7th Cavalry stumbled on June 25th, 1876. Only aware of the small camp of Cheyenne and Lakota before him Custer ordered his forces to attack. He hoped to get amongst the non-combatants in the camp and use them as hostages against the warriors.

This plan failed and Custer was faced with the enormity of the force arrayed against him. His forces retreated to a hill where they suffered the full wrath of the Lakota and Cheyenne counterattack. His party were wiped out. Only the remnants of Major Reno’s detachment, separated from Custer and badly bloodied themselves, survived to report on the Battle of the Little Big Horn. Of the almost 700 men who marched out with Custer less than two thirds returned. Though he had not taken part in the battle himself Sitting Bull had amassed the force that won this great victory.

Depiction of the Battle of the Little Big Horn on buffalo hide by a Cheyenne artist, circa 1878

Depiction of the Battle of the Little Big Horn on buffalo hide by a Cheyenne artist, circa 1878

The celebrations were short-lived, however, as public outrage at Custer’s defeat saw the US deploy thousands more cavalry to the region. This huge force hounded the Lakota, forcing many to surrender and breaking up any serious resistance. Refusing to surrender his weapons or way of life Sitting Bull led his band across the border in Canada in May 1877. Here he lived amicably with the authorities and even made peace with the Lakota’s old enemy, the Blackfoot. He stayed in Canada for four years until hunger and exhaustion forced him to return south.

Fears of Sitting Bull’s influence saw his band imprisoned and separated from the rest of the Hunkpapa for four years. In 1884, a year after his release, Sitting Bull toured Canada and the northern US and the following year joined Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show. His time in the limelight was brief, however, and after only four months with the Wild West show he returned home. A quite death was not to be for Sitting Bull and growing disquiet around the Ghost Dance movement signalled the end for the great chief.

Drawing on old traditions and practices this new Ghost Dance movement revitalised Native American communities and cultures across the US. This was a peaceful movement that promised peace and prosperity for the native peoples through unity and reunion with the dead. Yet the authorities feared any linking between Sitting Bull and this growing movement and ordered the chief’s arrest on the morning of December 15th 1890. In the ensuing arrest Standing Rock policemen Lieutenant Bull Head and Red Tomahawk shot Sitting Bull in the chest and head, he died later that day.

Patrick talks with a panel of experts about the life of Sitting Bull and his impact on history. Join us at 7pm as we revisit this man who was celebrated as a great warrior, a wise chief, a generous stranger, a holy man with ‘strong medicine’, and a loving husband and father. What was he like as a man? Has he become mythologised by history? Or is he really as great as the stories would have us believe?

Patrick also talks with Peter Hart about his latest book 'Fire and Movement' and its exploration of the British Expeditionary Force's role during 1914. A full list of 'Talking History' book recommendations can be found here.