I have dedicated my life to this struggle of the African people. I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons will live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal for which I hope to live for and to see realised. But, My Lord, if it needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die. - Nelson Mandela

102 years ago the foundations of South Africa’s current ruling party were laid. Three prominent South Africans—Sol Plaatje, John Dube, and Pixley ka Isaka Seme—brought together tribal leaders, religious representatives, and other prominent African intellectuals and figures to form the South African Native National Congress. Their aim was to promote and defend the rights, freedoms, and interests of the native people of the South African region. This task would, however, became harder and harder as time progressed and the surrounding political environment changed.

At the party’s inception non-whites made up roughly 1 percent of the electorate thanks to a series of restrictions on the franchise. After South African independence in 1934, however, this tiny minority became even more concentrated as successive governments enacted laws to dilute any non-white voice. Ironically this desire to further silence non-white political voices helped to extend the franchise as voting rights were given to all white men and women over the age of 21 by 1931.

Six years after this massive extension of the white voting population the few black voters on the common voters’ rolls were removed with the Representation of Natives Act, 1936. Though they would have their own ‘native voters’ roll’, this act all but annihilated what small political power the tiny black elite had had. Yet these acts only foreshadowed the coming total repression of the non-white South African population.

Though the ANC wasn’t entirely stagnant during South Africa’s first decades of independence, women were welcomed as associate members in 1931 and made full members in 1943, many began to see it as an out-of-touch ‘body of gentlemen with clean hands’. In 1944 this dissatisfaction came to a head when Anton Lembede and others, including a young Nelson Mandela, founded the ANC Youth League. This new guard had a strong African nationalist identity and began to campaign on the streets for rights and political representation for native Africans.

The League’s main weapons were peaceful campaigns of civil disobedience and strike action, which gained a lot of traction with the general African population. With this rise in popularity the ANC was forced to recognise the Youth League and reconcile with their progressive aims and methods. Lembede wouldn’t, however, be part of the Youth League’s takeover of the ANC leadership. In 1947 he died of cardiac failure, leaving the re-invigorating of the ANC to other figures like Albert Lutuli, Oliver Tambo, Nelson Mandela, and Walter Sisulu.

This increased politicisation didn’t go unnoticed, however, and became a key debate in the outcome of the 1948 General Election.

Since independence in 1933 South Africa had been led by Jan Smuts and his United Party. By 1948, however, Smuts and the UP had lost a lot of the support that had kept them comfortably in power for the past 15 years. In this close run race racial policy became a deciding factor amongst voters who were seeing a renewed politicisation of non-whites, which threatened the white political hegemony.

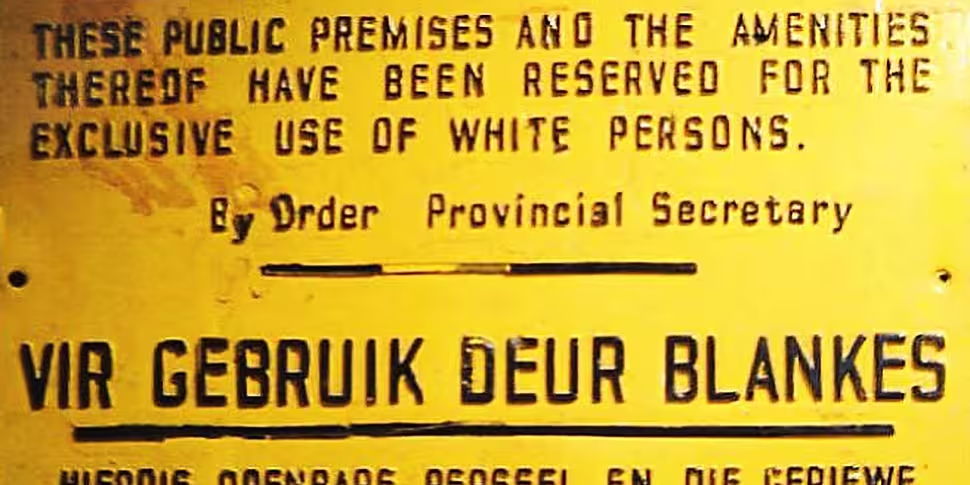

While the United Party advocated a vague ideal of slow integration of South Africa’s non-whites into the political realm the Reunited National Party campaigned on a platform of strong and total racial segregation, dubbed Apartheid. This policy of separation, literally meaning ‘apart hood’, found a great deal of support across the voting population and in 1948 general election the National Party took the highest number of seats and formed a coalition government with the Afrikaner Party.

The National Party’s victory wasn’t, however, unqualified nor was it won on Apartheid alone. Many South Africans were annoyed by the nation’s participation in the Second World War and the hardships that resulted from Smuts’ refusal to pursue a policy of self-preserving isolationism. Even then the United Party actually secured a majority of the popular vote in 1948, 49% compared with the NP’s 37.7%. This has led many historians to attribute the United Party’s loss, at least in part, to gerrymandering and the First Past the Post voting system.

It is impossible to know just how important the parties’ vying racial policies were to the outcome of the 1948 election, or what might have happened had the United Party remained in power; though studies on the Fagan and Sauer Commissions do give us some indication. What we know is that the National Party took office in 1948 and began to deliver on their promise of creating an Apartheid state. This would remain the case until 1994 when the ANC won a majority of seats in the first South African elections to include universal adult suffrage.

The National Party began the racial segregation of whites, blacks, coloureds, and Indians with the 1949 Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act. The following year Apartheid proper began with the Populations Registration Act, which officially defined the races and categorised people accordingly. The Group Areas Act and Immorality Amendment Act then built on this legislation, establishing different racial communities and making sexual relations between whites and non-whites a criminal offence.

Further restrictions on the working, living, and political lives of non-whites would follow as more and more Apartheid laws were passed; with the outlawing of loosely defined ‘communist’ activity denying non-whites any remaining official political avenues. This increasingly restrictive legislation, especially the Pass laws, was making the non-whites of South Africa foreigners in their own land. One unforeseen outcome of this campaign of separation, however, was its unifying of the non-whites who had previously been divided.

Before Apartheid there had been ethnic and cultural divisions amongst the various black, coloured, and Indian populations of South Africa. With the rise of this common enemy many of these communities banded together in an alliance of necessity, which became known as the Congress Alliance. At the same time the ranks of organisations like the ANC were swelling in reaction to the repressive legislation.

In 1952 this amalgamation of anti-Apartheid began a co-operative campaign of active and deliberate defiance of South Africa’s oppressive laws. Taking their cue from Gandhi and the Indian independence movement the Defiance Campaign against Unjust Laws adopted peaceful protest and passive resistance as their main weapons in the struggle against Apartheid.

Gandhi’s success, however, was dependent on the reaction of the international community and, more specifically, the British public to the campaigns in India. Lacking large-scale international coverage and the sympathy of their government’s voting public the Defiance Campaign achieved only limited success.

Despite this isolation in 1955 the Congress Alliance drafted a list of the aims and demands of the unrepresented and repressed people of South Africa. This Freedom Charter was read out in a mass rally later that year and adopted as the manifesto and core principles of the Congress Alliance and many of their anti-Apartheid allies. This Charter and inclusivity wasn’t, however, universal and in 1959 the Pan Africanist Congress split from the ANC in reaction to what they had seen as a dilution of the ‘Africanist’ struggle.

In 1960 this split changed the face of South Africa forever when the police opened fire on a PAC protest held in Sharpeville on the 21st of March. The ANC had planned similar protests against the Pass laws for March 31st, but the PAC hoped to steal the march on them. With 69 killed and many more wounded South Africa erupted in mass protest and violence and on the 30th of March the government declared a state of emergency. Thousands were detained and both the ANC and the PAC were soon declared illegal organisations.

Because of this outlawing and violence Sharpeville is seen by many as the starting point for the ANC's shift from passive to armed resistance. The following year the armed group Umkhonto we Sizwe, or the MK, was formed as ‘it would be unrealistic and wrong for African leaders to continue preaching peace and non-violence at a time when the government met our peaceful demands with force’.

It's also the point at which Apartheid truly entered the international stage as South Africa faced censure by the UN and the wider international community. While South Africa reacted by withdrawing from the international stage and isolating itself the world was now watching and attentive. In the following decades people and organisations around the world would try to effect change in South Africa through boycotts and other peaceful means.

Things wouldn’t, however, be easy or peaceful in South Africa. From the 1960s on South Africa was torn apart by civil strife. By the time the last of the Apartheid laws were repealed in 1994 political violence had almost become commonplace in everyday South African life. Today the wounds of apartheid are still healing and the scars from decades of racial violence and segregation boldly stand out on South Africa’s skin.

Patrick is joined by a panel of scholars and journalists as we find out how and why South Africa tried to separate the races and what the lasting cost of this policy was. Listen back as ‘Talking History’ takes a look at the history of Apartheid and the ANC.