Daniel Defoe was born in 1660 at a time of much upheaval across Europe. He is perhaps best known for his literary work ‘Robinson Crusoe’ but this was not published until he was 59.

During the earlier period of his adulthood, he was heavily involved in trade and statecraft across the continent. This flair for public life was honed during his early years.

While growing up in London his father, James Foe, was a relatively prosperous butcher and provided for his family’s needs. However, he was a Presbyterian dissenter who rejected the teachings of the Church of England. For this reason, Daniel was precluded from being educated at the more prestigious schools, such as Oxford and Cambridge.

He did receive a thorough education in the fields of the arts and sciences, under the tutelage of Charles Morton. He was seemingly on the path towards religious ministry, but his ambition directed him away from such a life.

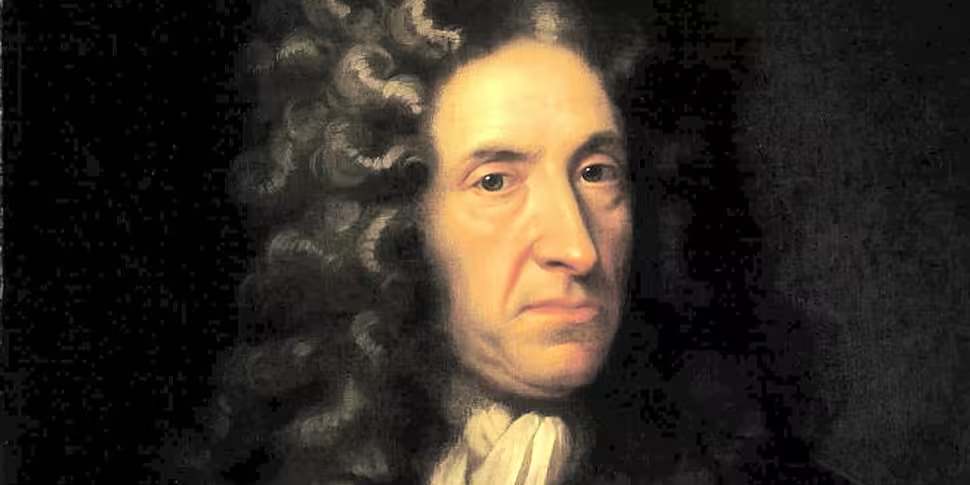

An image depicting the adventures of Robinson Crusoe

He began a career in business and added the prefix ‘de’ to his surname, giving it a more aristocratic sound.

This change in direction thrust him into the unstable world of politics and trade in early modern Europe. Though his ambition was unquestionable, his rate of success was murky to say the least. Defoe was rarely out of debt and moved from one project to the next, eventually bankrupting himself in 1692. These economic difficulties were due in no small part to Britain’s shaky relations with her European neighbours during this time.

He was also heavily involved in such political issues. His dissenting background primed him perfectly for such participation, as he regularly authored pamphlets outlining his stance on the various issues of the day.

He was involved in the Monmouth Rebellion of 1985, which unsuccessfully attempted to overthrow the newly crowned Catholic King James II.

‘The Morning of Sedgemoor’ by Edgar Bundy, depicting the final day of the Monmouth Rebellion

With the onset of the Glorious Revolution shortly after this, in 1988, he threw his weight behind the cause of William of Orange. This showed little loyalty to his Presbyterian origins, though William would prove to have relatively tolerant views on the question of religion.

Defoe continued to writing, often in defence of King William, demonstrated by his poem ‘The True Born Englishman.’ With the death of William in 1702, Defoe found himself persecuted for his beliefs once again.

Queen Anne acceded to the throne and began a crusade against non conformists. With Defoe to the fore in this regard, he quickly drew the ire of the throne, particularly for his pamphlets ‘The Shortest-Way with the Dissenters’ and ‘Proposals for the Establishment of the Church.’

He was arrested and brought to trial, ultimately suffering humiliation in a pillory and a prison sentence of undetermined length.

Daniel Defoe in the pillory

He gained release soon after in return for his services as a pamphleteer and intelligence agent for the Tories. He wrote under a variety of pen names and continued his work for them following their fall from power, but found it difficult to stifle his own views. For this, he continued to come into conflict with the political powers he railed against, spending more time in jail.

While continuing his political writing, Defoe now turned to fiction and is credited with popularising the art of the novel in Britain, most famously with his work ‘Robinson Crusoe’ published in 1719. This was the first of numerous novels authored by Defoe before his death in 1731, which, perhaps unsurprisingly, he endured while plagued by debt.

What was the true nature of Defoe’s political life? Why is he considered one of the foremost personalities of the early modern period? And what is the legacy of his prolific writing today?

Listen in to ‘Talking History’ as we address these topics and more.