After four years of arduous service marked by unsurpassed courage and fortitude, the Army of Northern Virginia has been compelled to yield to overwhelming numbers and resources – Robert E. Lee ‘General Order No.9’, April 10th 1865

On April 9th 1865 General Robert E. Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia to Ulysses S. Grant, commander of the Union Forces. This loss was the death knell of the Confederacy as most Southerners followed Lee’s example in the following months. By the end of May, besides a few rogue forces, the American Civil War was over and the Confederacy consigned to history. In this clash of North and South Lee and Grant proved probably the most important military figures, but which was the greater general and commander?

Union soldiers in trenches along the west bank of the Rappahannock River at Fredericksburg in the Battle of Chancellorsville by A.J. Russell, May 1863

Union soldiers in trenches along the west bank of the Rappahannock River at Fredericksburg in the Battle of Chancellorsville by A.J. Russell, May 1863

As states began seceding in early 1861 and America moved toward civil war Lee, amongst others, was faced with a crisis of conscience. He opposed any disintegration of the Union and seems to have been against slavery. The economy of his home state of Virginia, however, was built on cotton which in turn depended on slavery and on April 17th it joined the Confederacy. The following day Lee, already a highly regarded officer in the American army, was asked to help command the defence of Washington. Unwilling to ‘draw [his] sword upon Virginia’ Lee resigned on April 20th and joined the Virginia state forces three days later.

Though a reluctant rebel Lee would prove himself the ablest of the Confederate generals over the course of the war. In 1862, after months preparing the defences of Richmond and Savannah, Lee was given command of the Army of Northern Virginia. Though Lee took this first field command with the whispered nickname ‘Granny Lee’ he soon proved those who questioned his decisiveness and aggression wrong. In a series of bold offensives Lee drove the Union Army from deep in the South to within 20 miles of Washington DC.

A great deal of the Confederate success in ’62 was due to Lee’s bold and brilliant command. At Antietam he had concentrated his forces to turn what should have been a resounding defeat into a fighting retreat and at Fredericksburg his defences decimated the attacking Union army. It was at Chancellorsville though that Lee secured his legacy as he soundly defeated a force more than double his own.

Splitting his force, a high-risk military strategy, not once but twice Lee was able to steal the initiative and achieve local superiority of numbers at Chancellorsville. Though this ended up costing him his most able subordinate, and another tactical genius General ‘Stonewall’ Jackson, the victory at Chancellorsville was the high point of Lee’s career. Exactly two months after this victory Lee would fight and lose the Battle of Gettysburg.

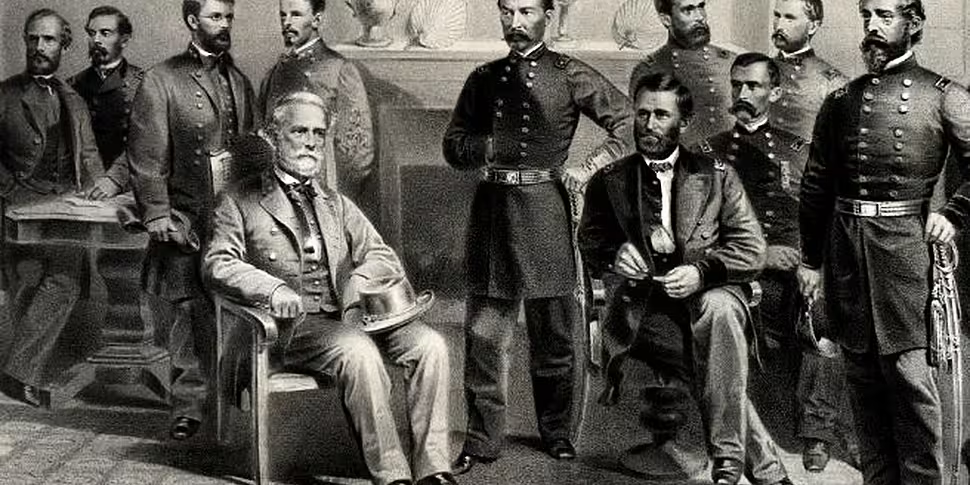

Photograph of General Lee (seated) with his son Custis (left) and Walter H. Taylor (right) by Mathew Brady, 16th April 1865

Photograph of General Lee (seated) with his son Custis (left) and Walter H. Taylor (right) by Mathew Brady, 16th April 1865

Though many see Gettysburg as the turning point of the American Civil War there are others who argue that Union victory was all but inevitable from the beginning. When war broke out in ’61 the North held the majority of America’s industrial and naval strength. General Winfield Scott devised the so-called Anaconda Plan to use these strengths to suffocate the South into surrender. While the navy blockaded Southern ports the Union unleashed armies in the west with the aim of disrupting production and supply and tighten the noose on the Confederacy.

Of the commanders in this Western Theatre Ulysses S. Grant stands out as the most accomplished. Though he had proved his worth as a commander leading untried volunteers in Kentucky, Grant’s legacy truly began with the capture of Forts Henry and Donelson. These strongholds secured the Tennessee River, giving the Union control over the vital water network and a platform from which to seize control of the Mississippi and thereby divide the Confederates.

As the navy secured the great river from the south and General Pope looked to push in from the north Grant moved to secure the railhead at Corinth, Mississippi. With these objectives secured only the fortress city of Vicksburg would stand in the way of Union control of the Mississippi. Before Grant could commit to Corinth, however, his forces were attacked at Shiloh. Caught unawares the Union camp was saved by an early warning of the approaching Confederates and quick tactical thinking by Grant and his commanders.

Though Shiloh ended in Union victory it proved ammunition for Grant’s detractors. An aggressive commander, Grant had been accused of using attrition to achieve victory regardless of the cost. The unpreparedness at Shiloh was seen as further evidence of Grant’s disregard for his men and rumours of drunkenness also began to spread. Grant was able to weather the storm of criticism from Shiloh, due mainly to his turning defeat into victory, and in the spring of ’63 took central stage in the long running siege of Vicksburg.

Grant at Cold Harbour, his heaviest defeat, Matthew B. Brady 1864

Grant at Cold Harbour, his heaviest defeat, Matthew B. Brady 1864

With the Western Theatre poised to fall Confederate generals and politicians called for support in the region. Lee instead chose to attack in the east once again. If his army could break out then Washington would be threatened and pressure for peace would begin to mount. Gettysburg put an end to this campaign and forced Lee to return south. Worse still for the Confederacy on July 4th ’63, just one day after Gettysburg, the garrison at Vicksburg surrendered to Grant. The South was now divided and the anaconda began to squeeze.

Grant had been central to the fall of Vicksburg and was made commander of the Western Armies as a result. He soon defeated the last major Confederate force in Tennessee, under General Bragg, opening the Deep South to invasion and paving the way for his promotion to General-in-chief. Leaving General Sherman as Commander of the Western Armies Grant moved east to take up his new role and put an end to Lee’s campaigning.

While the Western Theatre was strategically important it was in the east where the American Civil War would be decided. This was not only the political and historical heartland of the United States but of the Confederacy as well. Grant and Lincoln knew that defeating Lee in the field and seizing the Southern capitol, Richmond, wouldn’t bring peace though. They devised a plan of total war whereby the infrastructure of South would be targeted across the board; any asset, whether railroad, factory, farm, or mill, was to be denied the enemy.

This policy of total war was to be waged on every front with the aim of forcing the South to surrender. Grant oversaw the entire campaign, from Georgia to Alabama, as he campaigned against Lee in the east with General Meade and the Army of the Potomac. In May ’64 the two generals began their duel in earnest with the Overland Campaign.

'The Peacemakers' by George Peter Alexander Healy, 1868. Left to right: General Sherman, General Grant, President Lincoln, Admiral Porter

'The Peacemakers' by George Peter Alexander Healy, 1868. Left to right: General Sherman, General Grant, President Lincoln, Admiral Porter

Though Union forces usually came off the worse during this campaign Grant and Meade refused to retreat and continued to pressure Lee. While he was accused once again of callousness from his detractors, Grant knew that the Civil War had become a battle of numbers that the South could never hope to win. As the Overland Campaign came to an end Lee was forced to dig in at Richmond and Petersburg in Virginia or face losing the Southern capitol and his home state.

For more than ten months, thanks in large part to the massive trench system and defensive works he had built at the start of the war, Lee was able to hold out in what has become known as the Siege of Petersburg. Though they had once again inflicted much higher casualties on the North the weight of numbers and the lack of supplies and food eventually broke the Southern resolve. At the end of March, with both cities cut off, Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia retreated, leaving Grant and Meade to take Petersburg and Richmond.

The next time these two giants would meet was April 9th at Appomattox Court House where Lee surrendered to Grant and ordered his men to return to their lives.

Federal soldiers at the Appomattox Court House by Timothy O'Sullivan, April 1865

Federal soldiers at the Appomattox Court House by Timothy O'Sullivan, April 1865

While Lee’s tactical acumen was unparalleled during the war he had seemingly failed to see beyond Virginia and the Eastern Theatre. His decision to attack the North in ’63 left Vicksburg, the western Confederate States, and his own army vulnerable. The ultimate cost of this risk was the splitting of the Confederacy’s military power, the isolation of his own force, and—ultimately—defeat.

Though Grant was never able to get the better of Lee on the battlefield he was able to fight the war on a grander scale and marshal all of the North’s strength to bring victory. His exploits in the Western Theatre also prove he was no poor field commander. In the end, though he lost many battles, Grant won the war.

Join 'Talking History' as Patrick and a panel of experts try to determine who the greater general was, Lee or Grant. Was Grant too callous in his search for victory? Or was this attritional style an inevitable result of total war? Was Lee and the South destined to lose? Or did his loyalty to his state above all else cost him the war? Who do you think was greater, Grant or Lee?

This week also saw the first feature in the new 'Talking History: History of Art Night School' series as Patrick talked with Dr Francis Halsall of NCAD about the role of photography in the history of art. Patrick also talked with Timothy W. Ryback about his book 'Hitler's First Victims: And One Man's Race for Justice', a full list of 'Talking History' book recommendations can be found here.