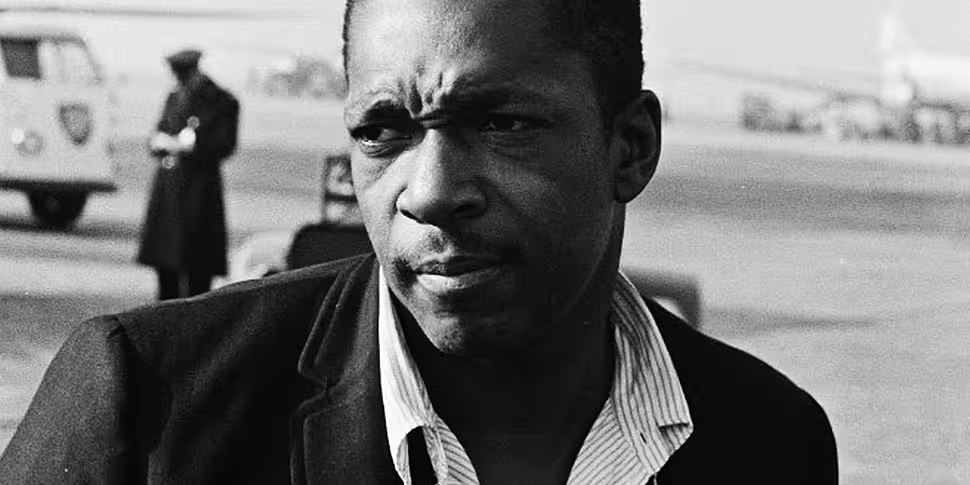

Attributed to an unnamed musician the above quote featured in the New York Times’ obituary of John Coltrane. Coltrane had achieved much in his brief 40 years though. He pioneered new forms and styles of jazz and left a vast discography behind, which continues to inspire people around the world today.

Born in North Carolina in 1926 Coltrane’s early life was beset by hardship and loss. At 12 he lost his father, aunt, and grandparents over a few short months. His mother left for Philadelphia soon after, leaving him as the man of the house. Though she did eventually send for him, this period of loss and responsibility was undoubtedly hard on the young Coltrane.

He seemed to find solace in music though. In 1943, Shortly after joining his mother in Philadelphia, Coltrane received his first saxophone, an alto. This gift from his mother was soon put to use and by mid-’45 Coltrane was earning money as part of a three-piece.

The Second World War was an ever present danger though and so, to avoid being conscripted into the Army, Coltrane joined the American Navy. His musical talent was quickly recognised and the Melody Masters, a base swing band in Pearl Harbour, quickly snatched him up. After a year of service Coltrane was discharged.

This had been far from a wasted year with Coltrane making his first recordings and rising in musical stature.

Back in Philadelphia, though, Coltrane was able to immerse himself in music free from military constraints. He began to play with pioneering figures like Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk, and (most importantly) Charlie ‘Yardbird’ Parker. While this allowed Coltrane to improve his own ability it also opened him up to the progressive and experimental side of jazz.

Alcohol and heroin had long been features of the jazz scene with many artists using them to cope with the hectic life of a musician or as inspirational aids. Coltrane wasn’t immune from their allure either and soon became dependent on both.

Both substances remained a problem for Coltrane for most of his early career. A religious experience in 1957 saw Coltrane radically change his life, including kicking both addictions cold turkey.

While Coltrane had been highly experimental for most of his career, pioneering modal and free jazz, his religious awakening brought an incredible depth to his music. As Dr Lewis Porter, author of John Coltrane: his life and music, put it: “[Coltrane] brought forth the idea that the music has such tremendous range, it’s for all kinds of emotional states including deep and spiritual states”.

This religious awakening and search for truth became infused with Coltrane’s music, each one feeding the other. His wasn’t a prescriptive spirituality though and Coltrane drew on a range of different philosophies, from Plato to the Buddha, for his music and thought.

Remembered as a prolific jazz pioneer with well over 45 recordings, John Coltrane’s greatest contribution is this infusion of music and spirituality. Join Patrick as he talks with a panel of musicians, historians, musicologists, and biographers about the life and music of John Coltrane.

What was his life like? How did he change jazz? Did his addiction to drink and drugs contribute to his death? How should we remember John Coltrane?