Catalonian independence has long been a thorny issue, one that has risen its head once again as the region looks set to hold a vote on independence this Sunday, the 1st of October, amid divisive circumstances.

Spain’s constitutional court has suspended the legislation on which the referendum relies while it rules on the legality of the vote. Yet Catalonia’s regional government has insisted the vote will go ahead. Meanwhile the national government has taken steps to disrupt the logistics needed to execute an effective referendum.

This is just the latest in Catalonia’s long history of conflict and opposition to central Spanish rule. One of the earliest chapters begins in 1640 when, with French aid, the region revolted against the increasingly draining and dogmatic rule of Spain’s Hapsburg kings. 22 years earlier Philip III had thrown Spain’s might into the burgeoning Thirty Years War.

Beginning as a war between Protestant and Catholic German states, this conflict became one of Europe’s bloodiest as it spread and engulfed most of Europe in sectarian and political violence. In 1635 Catalonia was thrust onto the frontlines as France declared against her southern neighbour, and disquiet began to fester.

Internal pressures in Spain had been building for some time though. Decades of war had placed massive financial strain on the Spanish treasury. Worse still her former Dutch territories had gained the upper hand in the long running Eighty Years War and the flow of wealth from trade and the New World had been stymied. As a result Madrid had tried to spread the cost of her Empire, carried mostly by the crown until now, across Spain. This was an economic burden the people did not shoulder happily.

It was the presence of Castilian soldiers on Catalan soil that proved to be the flashpoint though and, in May 1640, peasants revolted against the quartering of soldiers on their land. The rebellion gained momentum when Pau Claris, the President of the Generalitat of Catalonia, called the political bodies from across Catalonia to form an estates general. This body quickly began to enact its own laws and policies, which were to become the first steps towards independence.

Engaged across Europe, and with further rebellions in Portugal and some of her Italian territories, Spain found herself caught unawares by the Catalonians’ actions and unable to muster any swift response. This inaction emboldened Barcelona and the rift with Madrid grew as France wooed her newfound natural ally. With the promised protection of the French crown the Catalonians felt bold enough to declare themselves a republic on the 17th of January, 1641.

The response from Madrid to this move toward open rebellion was swift and a new Viceroy, Pedro Fajardo, was dispatched with 26,000 troops to bring the region to heel. Though resistance was met on the march to Barcelona it was easily overcome. Villages and towns, pacified through violence and the execution of rebel prisoners, were left in the wake of Fajardo’s passing, tracing a path toward the costal Catalonian capital.

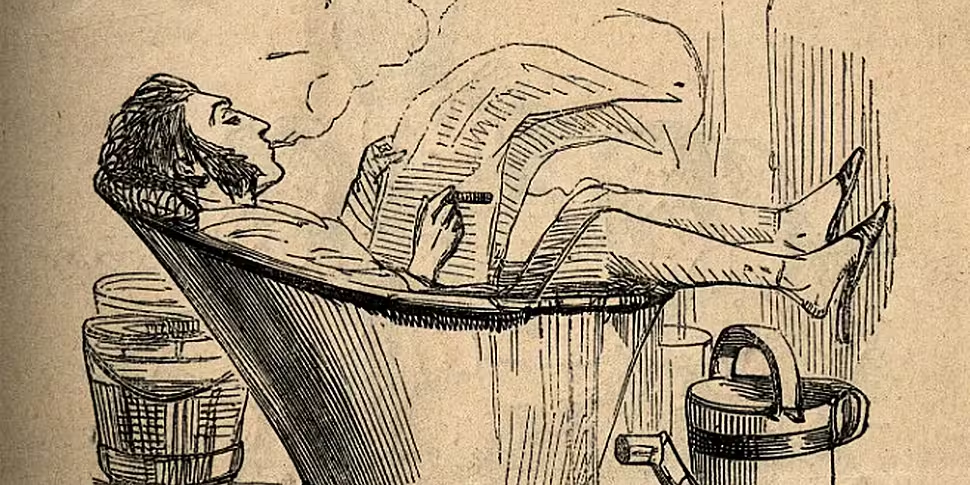

Though shocking today, such violence was routine at the time. Armies at the time were mercenary in nature and had little interest, or provisions, to spare for prisoners. The protracted wars of religion, raging for more than a century by this stage, had also fostered a tolerance for violence. In the Germanic north, where sectarian war raged between Protestant and Catholic enclaves, more than a quarter of the population died during the Thirty Years War.

The Catalonian Revolt formed a part of this tapestry of violence and many ordinary people suffered as Fajardo’s troops marched to meet the army of the Catalan Republic. The armies eventually met outside Barcelona, in the Martorell region, where the forces of the young republic suffered defeat. The violence inflicted on the country, and the threat to their capital, only served to entrench the Catalonian separatists further and they struck back in late January on the heights of Montjuïc.

Fajardo targeted the castle that dominated the heights, seeking to dislodge the forces within. The Catalonians fought ferociously against the larger Spanish army, however, repulsing every attack. The day firmly turned against Fajardo when a force of rebels sallied out from the capital below, scattered his army and forcing them to retreat along the coast for safer shores.

The Catalonians were unable to capitalise on this momentary advantage, however, as they struggled to come to grips with internal strife and conflict. Fajardo’s march to Barcelona had added fuel to the peasant revolt, which had ignited the rebellion itself the year before. The Catalonian Generalitat struggled to contain and direct this increased discontent, that began to be directed toward itself and the local nobility.

Worse still for the burgeoning republic was the death of its first president, Pau Claris.

Just a little over a month after declaring the Catalan Republic, the 55 year old Claris fell ill and died. Though he had been sickly for a year or more, suspicions of foul play immediately surround Claris’ death. A strong willed and popular politician, Claris provided an ideological backbone to the Catalonian Republic. His death left a vacuum that France’s King Louis XIII readily filled, thanks in large part to his military commander Philippe de La Mothe-Houdancourt; who had fortuitously arrived the day Claris fell ill.

With the military support of their new French liege, the Catalans pressed their advantage against their Spanish neighbours. It soon became clear though that France had little interest in the Catalonia beyond its strategic location, and support for the French began to wain in the war weary region.

Though they had set out seeking independence the Catalans found themselves, again, relegated to a theater of war for the French and Spanish kings. For over a decade the two powers fought for control of the region with fortunes swinging back and forth between the two. The Peace of Westphalia brought peace between Spain and northern Europe, leaving her free to concentrate on France.

With the balance of power firmly in Spain’s favour she was soon able to retake most of Catalonia, with Barcelona eventually falling in 1652. The Pyrenees proved an impenetrable border, however, and the Spanish were never able to retake Roussillon, the region north of the mountain range. The Treaty of the Pyrenees brought peace between Spain and France in 1659 and established the border between them that has lasted to this day.

National identities are incredibly complex. Shaped by geography, language, history, culture, politics, and religion the idea of “us” can often lead to violence and suffering as people seek to carve out their own national homelands, or hold onto regions that threaten to secede. This was the case in Catalonia in 1640, and in countless other places since.

Tonight Talking History will explore one such search for an independent homeland as Patrick Geoghegan leads a panel of experts in a discussion on the history of the Raj, on Newstalk from 7pm.