the nature and all the circumstances of [the slave] trade are now laid open to us; we can no longer plead ignorance, we can not evade it; it is now an object placed before us, we can not pass it; we may spurn it, we may kick it out of our way, but we can not turn aside so as to avoid seeing it; for it is brought now so directly before our eyes that this House must decide, and must justify to all the world, and to their own consciences, the rectitude of the grounds and principles of their decision - William Wilberforce

Earlier this year 14 Caribbean nations began legal proceedings against the governments of France, Britain, and the Netherlands seeking reparations for the slavery employed by these nations during their colonising of the Caribbean and the resulting damage which, it is being argued, can still be felt today. Like other reparation debates, this move raises the issue of generational guilt and the plaintiffs must prove why current governments should shoulder the blame for their ancestors' actions.

As much as the onus is on the Caribbean nations, and their representatives, to prove why France, Britain, and Holland should pay for these century old crimes, those nations who once dominated the globe must also acknowledge the price of their historical grandeur. Most historians and commentators would agree that the slave produced cash-crops and the international slave-trade itself were key in financing the affluence of the Georgian era and helped pave the way for the industrial revolution and enlightenment thinking.

Following the success of the Portuguese and Spanish experiments in South America the other European powers launched colonial expeditions to the newly discovered continents. While North America and the islands of the Caribbean Sea didn't have the caches of gold found by conquistadors in South America, they provided the perfect climate for sugarcane, coffee, tobacco, cocoa, and cotton. Throughout the 17th century land was cleared for plantations of these lucrative cash-crops. The increasing demand for cheap labour wasn’t, however, being met by the existing modes of slavery or indentured servitude.

It was to Africa that Europe looked as a reservoir of potential labour and soon the Atlantic slave-trade exploded. The British led the way as they, the Portuguese, French, and Dutch opened massive markets for human chattel. Historians have illustrated how willing European buyers and their deep purses resulted in an increase in slaving as slavers worked to meet the growing demand. During the 18th century as many as 50,000 men and women were being transported from Africa on an annual basis. But why were so many fresh slaves needed each year? And why were they all coming from Africa?

The truth is they weren't all coming from Africa. Indentured Europeans and the surrounding native peoples were also being sent to work on plantations. But for a variety of reasons African slaves were the preferred form of labour. With most of the indigenous populations wiped out by war and disease labour in the Americas would have to come from abroad. With a similar shortage of indentured Europeans Africa was the natural port of call. More important was the fact that there was a more ready supply of slaves in Africa than elsewhere due to combined African and European slaving in the continent. This was vital to the plantations where death ensured a continual decline in the labour force, especially in the main industry; sugar production.

The easily accessed energy in sugar makes it naturally appealing and addictive to humans, yet until the discovery of the New World it wasn't an easily acquired resource. With a perfect climate for sugarcane the Caribbean allowed for the explosion of this industry. Sugar production was very intensive, however, as the hardy stalks are grown in tropical heat then harvested and fed into machines which squeezed sugar from the pulp; this runoff was then boiled down and refined over great fires. Neither the fires nor the machines could discern man from plant and limbs were pulped and bodies accidentally burned on a regular basis; this industry consumed men, cane, and lumber alike.

While the high death toll from malnutrition, disease, and the working conditions increased the demand for African slaves it was their emphasised otherness which allowed for the terrible cruelty which would become synonymous with slavery; especially in the Caribbean and South America. The human brain naturally notices and differentiates based on race and gender, in fact they are the first things we seem to notice. The 17th and 18th centuries saw the emergence of racial theories as people used these immediately identified differences in skin to justify slaving and to drive wedges between white labouring Europeans, black slaves, and native peoples.

Though there were moves to recognise the humanity of these people who were 'other' but clearly human, the profits from slavery and slave generated cash-crops were too high to forgo the practice of owning other people; even if they claimed kinship through Christianity. So terrible in fact was the treatment of slaves in the Caribbean and South America that slaves themselves became a key import to these regions as new bodies were needed to replace those lost to mistreatment; which included but wasn't limited to flogging, rape, amputation, branding, and many worse practices.

This demand for slaves was key to the Atlantic triangular trade; slaves were brought from Africa to the plantations in the Americas, the same ships then carried slave produced materials to America and Europe where they were made into goods which were then sent to Africa to trade for slaves, and the cycle began again. While slavery, the slave-trade, and the dehumanising and mistreating of other people weren’t new phenomena the 17th to the mid-18th century saw their employment on an industrial scale. This scale of slaving and mistreatment of slaves would lead to the downfall of the Atlantic slave-trade.

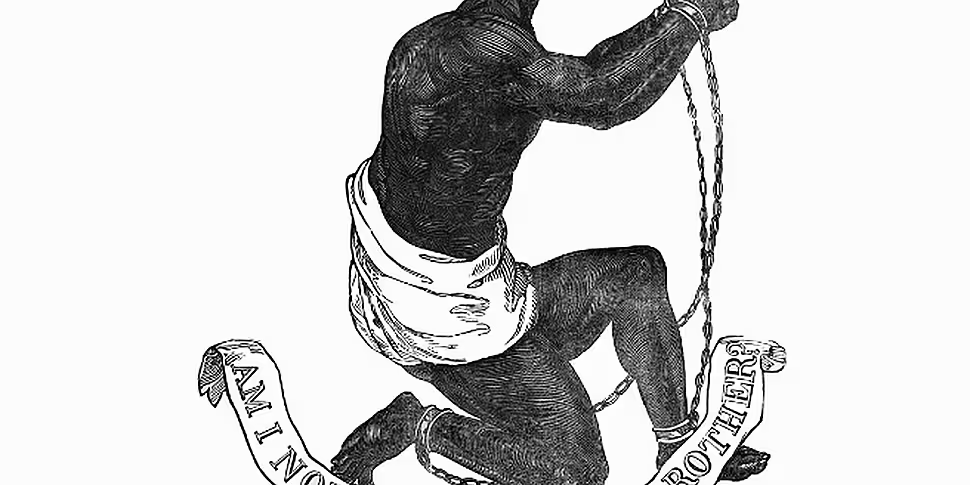

Though for centuries European powers had used the bible to justify slavery, even in the face of papal bulls, the growth of the Atlantic slave-trade and the realisation of the inhuman conditions and practices being employed in its execution led to the rise of the abolitionist movement. It was mainly Quakers and evangelical religious groups that began to denounce slavery as they saw it as naturally un-Christian and from this religious opposition the abolitionist movement grew. Britain, the largest imperial power in the Caribbean and the greatest slave-trading power, was the epicenter of the abolitionist movement as a divide emerged between those who supported and those who opposed this cornerstone of the British Empire at the time.

As time progressed the abolitionists’ voices became louder and were joined by Enlightenment thinkers whose more secular minds railed against this violation of the rights of man. It seems as though the influx of capital from slavery allowed for the growth of urban society and industry which birthed the Enlightenment which in turn denounced slavery. The abolitionist movement wasn’t, however, an overnight success and the struggle for the emancipation of man was a slow and arduous journey. Just as Britain proved to be vital to the explosion of the Atlantic slave-trade so too did she prove to be the vital force in its destruction.

Though Spain had disavowed slavery in its territories with the 1542 ‘New Laws’, these were largely disregarded and were only extended to the indigenous Amerindian people. It was in 1772 when a British court ruled that James Somersett, a newly baptised escaped slave, could not be transported against his will that a precedent for a human right to freedom was established. This ruling proved the starting block for abolition as Knight v. Wedderburn (1778) did away with slavery in Scotland. Slavery still existed, however, in the British West Indies and the 13 American Colonies and so a group of Quakers founded the first British abolitionist organisation in 1783.

The abolitionists urged an end to slavery by highlighting the conditions which slaves suffered both in transit and on the plantations. They published pamphlets and held talks which highlighted the real cost of sugar and began to change popular attitudes towards slavery and the slave-trade. This proved inadequate against the financial rewards being reaped by the Atlantic triangle trade and it wasn't until 1807 that Britain outlawed the international slave-trade, though slavery itself wasn't abolished until the 1st of August 1834 when all slaves on British or Imperial soil were emancipated.

The decision to outlaw the slave trade was influenced, at least in part, by Napoleon’s decision to reinstate slavery in its territories, the 1804 Haitian revolution, and the on-going Napoleonic Wars. The Abolition of the Slave Trade Act not only portrayed the British in a better light than their European opponents but it also provided legal justification for the search and seizure of vessels on the high seas, including merchant vessels that might be aiding the French and their allies. Whether it was a document of war or humanity the fact is that after decades of campaigning the abolitionists had achieved a great but limited victory.

William Wilberforce had been the champion of the abolitionist cause for 26 years and he, and his allies, continued to lobby for full abolition both at home and across the globe well after 1807. Their actions contributed in large part to the establishment and bolstering of the West Africa Squadron, to the ending of the international slave-trade, and to the eventual end to slavery across the British Empire. Wilberforce died three days after the passage through Parliament of the Slavery Abolition Act 1833 was assured, it was enacted the following year.

Yet slavery on British soil still exists, as it does around the globe. Though Atlantic slavery is probably the best known example of men claiming ownership over one another this practice has never been limited by time, geography, or law. Yet we are quick to dismiss slavery as a practice of the past. While it is no longer the open practice which saw Saint Patrick captured and carried to this island or Rome and Egypt rise to greatness slavery still exists around the globe, generating revenue and producing cheap products every single day. There is still a lot to do to rid the world of slavery.

Listen back as Patrick talks with a panel of experts about the history of slavery in the Atlantic and Ireland’s role in its establishment, continuation, and eventual abolition. How important was slavery to global commerce? What was the difference between slaves and indentured labourers? Were the conditions different? And did they band together or did they divide themselves along racial lines? What role did the Irish play in all of this? And what is the legacy of slavery today?