In 1871 the final stages of German unification were concluded with the Treaty of Frankfurt. Prussia had been the leading force behind this drive for a new Reich and became the premier power in the resulting German state.

This region was known for its industrialism, martial tradition, and pragmatic mindset and its ascendency saw these traits dominate the international perception of Germany. The Wars of Unification and later World Wars combined with this Prussocentric identity to ensure industrialisation and total war would dominate popular histories of modern Germany.

Yet the German Empire also proved to be one of the most progressive states during the 19th and early 20th centuries; one in which social, artistic, and philosophical revolutions took root and flourished. Though these movements were stalled by the First World War and its insatiable appetite for money, men, and materials the conflict also provided the opportunity for even greater change.

Four years of total war had shattered Germany, overthrowing the ideologies that had dominated since unification and challenging the nation’s very identity. Out of this ruin emerged the Weimar Republic.

Lasting only fourteen years this new state oversaw massive political and cultural reform while cradling the nation through the tumultuous post-war period and Great Depression. By the time Hitler rose to power Germany had become a world leader in science and film and a hotbed for experimental and provocative art.

A still from 'The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari', 1920

German expressionist cinema is one of the most famous movements from this period. The First World War had isolated Germany from the rest of the world and it had to look inwardly to provide entertainment for the masses.

The resulting surge in domestic filmmaking was free from international influences and instead reflected German art trends. Expressionism had come to the fore in Germany before the First World War. With a focus on emotions and the subjective experience this movement depicted abstract and distorted visions of the world.

Expressionism took off internationally with various iterations across Europe and the United States. It was in its native Germany, however, that the movement was strongest and where it made the transition from theatre and art to the silver screen. After the First World War this movement came into its own as money starved productions relied on innovation and creative set design to make movies. Unlike the growing Hollywood industry, German filmmakers were also intent on dealing with the psychological trauma of the First World War.

These factors combined so that the surreal became commonplace in German cinema. Sets were used to reflect and accentuate the emotional states of characters while unrealistic tales and settings allowed for unfettered exploration of emotions. As a result this movement created some of the first, and greatest, horror and sci-fi movies and also helped lay the foundations for the rise of film noir.

The legacy of ‘Nosferatu’, ‘The Cabinet of Dr Caligari’, and ‘Metropolis’, to name but a few, can still be felt in the world of art and cinema today.

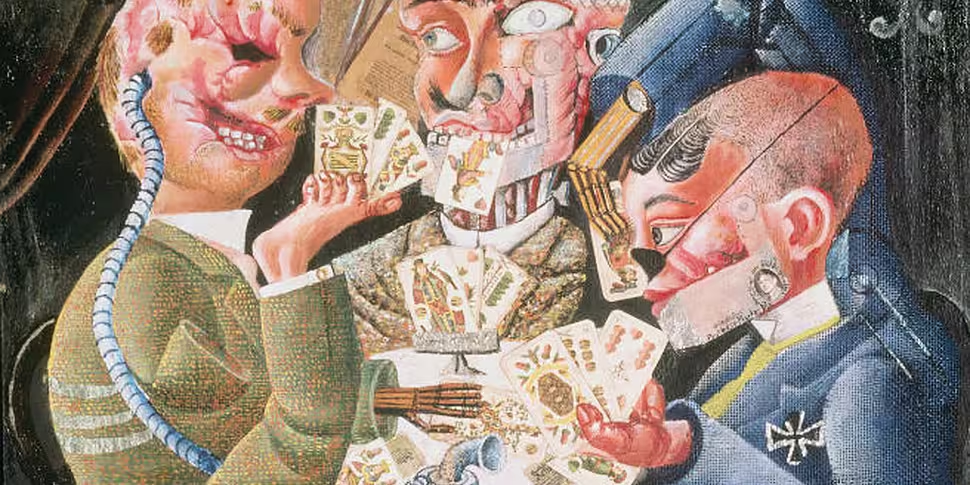

Expressionism wasn’t simply limited to the silver screen in Weimar Germany and it also flourished in art, dance, and literature. In these fields, however, it faced strong challenges and contention from the new schools of art like Dada and Bauhaus. Where the former was a European wide movement that eschewed tradition and challenged the very concept of art itself the latter was distinctively German and aimed to create a new school of art that stretched across all mediums.

Despite these differences both movements were born in reaction to the perceived futility of the art that dominated before the First World War. Where the Dadaists reacted by revelling in the absurd, however, Walter Gropius and Bauhaus preached for functionality to dominate art. This focus on the practical and its centralising around 3 major schools—in Weimar, Dessau, and Berlin—saw Bauhaus flourish during the 1920s and ’30s. In contrast the anarchy of Dada saw the movement dissipate and peter out; leaving behind one of the strongest legacies in art.

A part of the New Objectivity movement Bauhaus’ focus on functionality was eagerly welcomed by the rebuilding Weimar Republic. The cost of war and peace had left the German economy crippled and its people starving. Though there was still room for expressionism and its thoughtful reflection on emotions the harsh austerity of Weimar Germany was soon reflected in its art. In sculpture and architecture this movement was defined by Bauhausian uniformity and practical lines while its artists and photographers turned towards political satire and social commentary.

The logo of the Bauhaus movement

This popular engagement with politics was rampant in Weimar Germany where even the cabaret halls were overtaken by dark social satire. Nowhere were these cultural trends more evident than in the capital, Berlin. The seat of German government and a hub of power and wealth this city had been a beacon for the industrious, artistic, and desperate. The post-war period, however, saw a new fervour take root in Berlin as the city was caught up in the economic boom of the Roaring Twenties.

The First World War had created a break in history for the belligerent nations. The time before 1914 was firmly part of the past and the modern age of democracy and freedom had begun. New fashions and tastes identified the new groups of young people that were springing up during the Roaring Twenties. Eager to enjoy life to the full these groups were immortalised in their hedonistic glory by the writings of F. Scott Fitzgerald and Evelyn Waugh.

Berlin became the mecca for Germany’s ‘Bright Young Things’ as people flocked to the capital, eager to join the brave new world. The nation’s existing moral codes were challenged en masse while academia and the arts flourished in this avant garde atmosphere. This soon saw the capital earn a reputation for decadence and excellence as its night life became increasingly raunchy while figures like Albert Einstein ensured the University of Berlin led the way in the sciences. These trends were aided by the increased tolerance towards Jews and other minority groups in Weimar Germany.

Marlene Dietrich in 'The Blue Angel', 1930

Marlene Dietrich in 'The Blue Angel', 1930

Though the Weimar Republic was a time of great change the period was not without its detractors or opponents. Despite this resistance, however, German society and public attitudes had changed greatly by the 1930s. Artistic tastes had been revolutionised, morals had been recast, and a modern progressive German identity had been cast from the embers of the German Empire; even voting to decriminalise homosexual acts between men in 1929. All of this came to an abrupt end in October 1929, however, when the American Stock Market came crashing down.

The progress of the Weimar Republic and its economic recovery had been facilitated by low interest loans and investment from America. The Wall Street Crash put an end to these programmes and Germany entered into economic ruin with one of the worst periods of hyper inflation in history. Though successive Weimar governments made great leaps toward stabilising the economy this collapse opened the door for the extremist political parties.

In 1933 Hitler became Chancellor of Germany and began the establishment of a totalitarian Nazi government. This Third Reich quickly stamped out the alternative cultures that had flourished during the Weimar Republic, reasserting the caricature of Germans as pragmatic and industrious militarists. Ironically this helped to perpetuate these cultures as leading thinkers, artists, and philosophers fled the fascist jackboot; exporting their ideas to the land to which they fled.

The Reichstag on fire, 1933

The Reichstag on fire, 1933

Peter Gay’s seminal ‘Weimar Culture: the Outsider as Insider’ stands out as one of the best books written on this cultural and intellectual movements of this period, while Eric D. Weitz’ ‘Weimar Germany: Promise and Tragedy’ tells of the rise of this state and its eventual fall.

For a full list of ‘Talking History’ book recommendations click here.